Over the past year, I’ve thought a lot about my mom, who died in 2008. I’ve often wondered, how would she—an older Latina with underlying comorbidities and a deep, abiding love

of socializing—navigate a global pandemic?

More recently, with the hope brought on by increased vaccinations, I’ve thought about how glorious this weekend would have been, how many selfies we would have contributed to the steady stream of gratitude and joy that floods my social media feed every second Sunday in May.

Since her unexpected death 13 years ago, Mother’s Day has lost some of its brunch-and-flowers innocence for me. I still spend the day celebrating with my son, who was born four years after my mom died, and honoring other moms I know and love. But even more so, perhaps, it’s a day I spend thinking about the group of women who showed up the day my mother left, and have lifted me up ever since, more so than they probably realize.

This group of women—I’ve come to call them Las Amigas—were my mother’s dearest friends. And while, of course, they could never replace her, they’ve served as proxies, providing unfettered, unconditional love when I’ve needed it most.

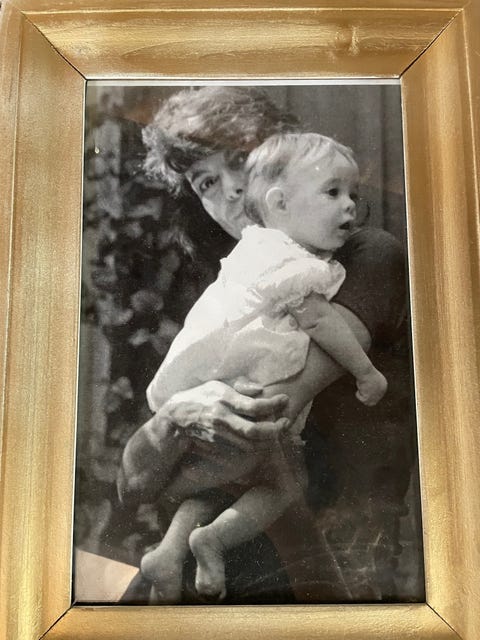

Psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner, who helped create the Head Start program in the United States under President Johnson, famously said, “Every child needs at least one adult who is irrationally crazy about him or her.” For my siblings and I, that irrationally crazy adult was our mother. With my older brother and sister in tow, she fled Cuba in 1960, shortly after Fidel Castro took power during the revolution. Seeking refuge in the United States, they took a ferry from Havana to Key West, then traveled via train to New Orleans, finally settling in New York.

Throughout our lives, our mom showered us with unrelenting love and support. And every professional success I’ve had is due in no small part to her fierce belief in my potential—and my own internalized desire to make her proud. But when your biggest cheerleader dies, who picks up the megaphone?

As I struggled to regain my footing after losing her, I searched for people who could fill that void—people who had my back, but who could also share stories I’d never heard about my mother. I found a support group in Las Amigas—five incredibly cool, independent, and strong women who knew me as just one facet of my mom’s multidimensional life.

In Cuba, my mom lived in a multigenerational home, as was the norm. In her case, she was raised by aunts and great-aunts. Years later, while my family was living in Atlanta, my grandmother occupied the bottom floor of our row house. I suspect that growing up with older relatives predisposed me to being able to navigate adult spaces as a child, and it also might explain the ease with which I was able to reach out to Las Amigas when I needed their support.

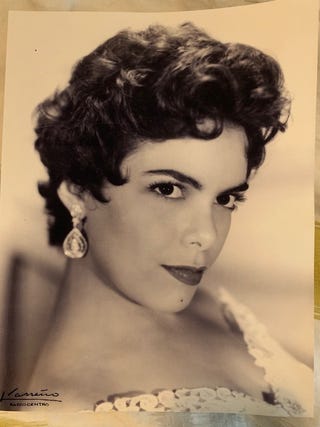

Even as a child, I realized my mom’s friends were both book and street smart, glamorous and worldly. I knew that when Mireille left Cuba, she worked at Bergdorf Goodman in New York. She’d married a movie distributor, spent time in Cannes, and refused to give up smoking well into her later years. She was my mom’s oldest friend, two pretty girls who’d met in kindergarten at Havana’s Merici Academy, where the strict Ursuline nuns left a lasting impression. When my husband’s book came out in 2013, my mom wasn’t there to share in our excitement. But Mireille was. She requested a personalized copy, and upon finishing it, wrote a beautiful letter to me detailing her favorite parts.

Mom met Celie as a teenager in Cuba. After the revolution, Celie settled in Madrid. Visiting her was our first trip to Europe, a gift from my brother. My Mom and Celie had partied with Hollywood stars like Kirk Douglas back in the 1950s in Cuba, so when Celie heard Bruce Springsteen was in Madrid and staying at the Hotel Ritz, she took us there. As we sat in the marbled lobby, The Boss exited an elevator with his wife and bandmate, Patti Scialfa. My mom, full of charm and dressed in a standout Krizia suit, called out to him like they were old pals. Surprised, he turned, waved, and gave the gawky starstruck teen standing next to two tall, striking women a huge smile and an everlasting memory. Years later, when I was struggling with infertility after my mom’s death, it was the devoutly religious Celie who prayed for me to Our Lady of Lourdes.

"My mom, full of charm and dressed in a standout Krizia suit, called out to him like they were old pals."

One of the first friends my mother made upon arriving in New York was Zigrida, a Latvian woman who’d fled Nazi occupation as a child by walking west for months and hiding in a network of safehouses. Zigrida and mom would go on cruises together—they loved an hours-long, multi-course meal. When we could no longer break bread with my mom, my husband and I would cook elaborate meals for Zigrida, who would listen intently as we discussed our jobs and dreams.

My mom met DeeAnne at the University of North Carolina library where they both worked—and where they were occasionally mistaken for models due to their fondness for wearing miniskirts and platforms. My father was pursuing his PhD at the university, and my mom and DeeAnne bonded over having married volatile men who were praised for their brilliance. It was the 1970s, and they explored feminism together, guiding each other through the process of finding their own voices. When my brother died just a few months after my mom, it was DeeAnne who helped arrange his memorial service at her church in Miami, near my brother’s home.

Once my mom found her calling as a minority and immigrant rights advocate in Atlanta, she also found a kindred spirit in Aida, a glamorous philanthropist and politically left-leaning Puerto Rican. Aida and my mom loved to salsa dance and recap stories from The New York Times, roiling each other up over Republican agendas and Latin politics. Together they advocated for Atlanta’s Latin population—a community that, especially in the ’80s and ’90s, lacked representation. When I didn’t have anything black to wear to my mother’s memorial, it was Aida who bought me a dress, a perfectly chic black DVF that I loved as much as I hated. I never wore it again.

I came across a study recently that suggests having friends who are at least 15 years older helps individuals appreciate life experiences. On the flip side, older people report benefiting from the fresh perspectives that younger friends provide. I’ve learned first-hand that there’s so much more to these unique relationships beyond the transactional. Over the last decade, I’ve stayed in touch with some of these friends—they are mine now, too, not just my mom’s—more than others. But I hope they all know how much they mean to me. This Mother’s Day I’m thankful for Las Amigas, women who in my mom’s absence gave me some much needed “irrational crazy.”