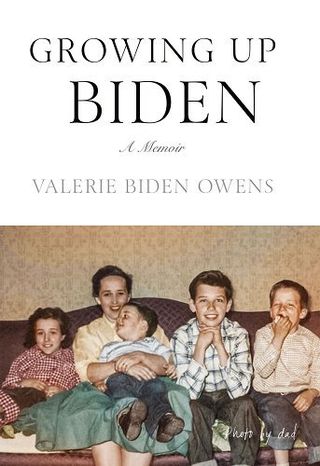

“People in Washington know that Valerie Biden Owens is the most powerful woman in politics that most people have

never heard of,” says Deb Futter, publisher of Biden Owens’s new memoir, Growing Up Biden. We do know her on some level—she’s the sister of the President; she shares his smile, name, and messaging. But could we spot her in a grocery store aisle? Do we know that she was one of the first women to run a Senate campaign and remains one of the closest people to our sitting leader? Are we aware that her ideas have shaped his platforms and her warmth helped raise his sons?

Biden Owens has largely avoided press and participation in several major profiles written about her. Growing Up Biden is in many ways her true unveiling to the world. But at the book’s core is a familiar Biden theme: the loyal, faithful family—one that might seem too loving to be true if we hadn’t seen the extent to which each member has been tested. The beating heart of President Biden’s life and career has always been family. We’ve seen it time and time again. The image of his 1973 Senate inauguration, held in the chapel of a Delaware hospital, remains indelible nearly 50 years later. His son, Beau, was still hospitalized with injuries from the car crash that killed Biden’s wife and daughter only weeks earlier, and Biden refused to leave him or his brother. Through all the pain and victories, Valerie has been steadfastly by his side. “You can’t share in the joys and then not share in the sorrows,” Biden Owens tells ELLE.com.

Growing Up Biden speaks to the Irish Catholic experience—the large family, the joys, the heartbreaks—but it also examines the life of a woman in politics. Writing it required a posture that felt unfamiliar to Biden Owens, she explains. “The part that was hard is [the attitude of] the Irish Catholic school kid who [is] never supposed to talk about me,” she says, as we sit in the front room of the University of Delaware’s Biden Center, where family photos spanning decades are displayed across the mantle, shelves, and tables. The focus on herself felt contrary to her beliefs and the way she was raised—but it was the very intention of the book itself. “‘And then I did this, and I’m really important to my brother, and then I, I, I, I.’ That was the hard part.”

When Joe Biden, then a lawyer and not yet 30 years old, decided to run in the 1972 Delaware Senate race, he turned to Biden Owens, his younger sister by three years, to manage his campaign. “I said, ‘Joey, I don’t know anything about running a statewide campaign.’ And he said, ‘That’s okay. We’ll figure it out,’” she remembers. “What we had to figure out is that we had no influence. We had no money. We had no power. We knew no one in power, and the Democratic Party in the state of Delaware was not very strong. We were a conservative state, and we didn’t have the party to rely on.” Biden Owens was a teacher, as was Biden’s then-wife Neilia Hunter Biden. The voting age had recently been lowered to 18, and the youth were becoming increasingly politically engaged.

“I told my kids, my students, that they could learn about social studies and politics in the classroom, or they could come out and experience it firsthand,” Biden Owens says. “My brother came to the school and spoke to an assembly, and he was young, vibrant.” She describes producing makeshift newspapers in lieu of glossy campaign literature and recruiting teens to distribute them. In a year when Democrats were overwhelmingly defeated, Biden became a U.S. senator by just over 3,000 votes. Biden Owens credits the kids.

“Humiliation has a long shelf life.”

Relatively few people outside the Beltway recognize that Biden Owens, who ran each of her brother’s Senate races and his 1988 and 2008 presidential bids, was one of the first female campaign managers. That doesn’t concern her. “I have plenty of recognition for it,” she says. “The recognition I have for it is that Joe was elected. That’s all the recognition I need. Even when I ran the Senate campaigns, [there were] very, very few female campaign managers. All the pundits were men. The reporters, with few exceptions, were all men. It was a man’s playground, and women were relegated to opening and closing the headquarters and getting the coffee.” Having a brother—hers in particular—running the show gave her a clear way in. “My brother pulled up a chair for me at the table, and literally our table was all men. He said, ‘This is my sister. She speaks for me. If she says it, consider that’s what we should do.’ That made it a lot easier for me than a lot of other women who had to pull up a chair.”

The sibling relationship can offer a huge degree of security compared to the candidate-campaign manager relationship, Biden Owens insists. (Vice President Harris similarly turned to her younger sister Maya to chair her own 2020 run.) “The biggest asset is complete trust…because of the trust that existed between us, my brother didn’t have to worry about anything that happened back at the headquarters: what was going out, what was being said, what was being printed, what was the radio ad. He didn’t have to worry about that. All he had to worry about was going out and being the best Joe Biden that he could be.”

From her vantage point as one of the closest people to the President, Biden Owens has unique insight into his mind, both in and out of the Oval Office. What does she wish the public could see about her brother? “I think one of the things that I read [that] is negative is if he falters on a word—and he’s a stutterer,” she says. “From the time he was a little boy, he stuttered. This kid, he couldn’t string more than three words together at a time. So, I think when you see him pausing and the unpleasant people in this country, the right wing, Trump people say, ‘Oh, look at him. He doesn’t know what he’s talking about,’ it is remnants of when he was a kid and stuttered,” she says. “Humiliation has a long shelf life.”

Those who stutter will see themselves in the book. Biden Owens hopes that others will, too. Single fathers, the loved ones of addicts, those who’ve lost someone to cancer, anyone who’s grasped a parent, child, or sibling tightly as they struggled. (I personally connect with the embarrassment, the frustration, and isolation that comes with my own intermittent stutter.) “I’m a storyteller,” she says. “What would give me great pleasure is if a reader picks up the book and she says, ‘Oh my God, that’s me. She gets me. Oh, that sounds like my dad.’ If there’s a connection, that would give me a great deal of pleasure.”

“We’ve been in this business for a while. Politics is a noble profession, and I keep reminding myself of that.”

Creating compelling narratives was part of Biden Owens’s work on the seven Biden Senate campaigns, as well as the career she pursued outside of that. For 20 years, she worked alongside Joe Slade White, who is credited with revolutionizing television campaign advertising through his work as a consultant for the Biden team, among other politicos. In 2014, she became a resident fellow at Harvard’s Institute of Politics, creating a class called Politics: Up Close and Personal, which was comprised of six students who she taught at her apartment. She served as an advisor to the United Nations General Assembly from 2016 to 2017 and worked with Women’s Campaign International. She also serves as the chair of the Biden Institute. But, she insists, it really all has been about Joe. “My number one job is raising an older brother,” she says. “I must say, I think I did a pretty good job.”

For the 2020 presidential election, Jen O’Malley Dillon served as Biden’s campaign manager while Biden Owens worked as a national chair. Ceding the position was easy, she says. “I am and always have been his best friend, his advisor, his confidante, and his sister, so we always talk, and we bounce ideas back and forth. But not being the campaign manager, I didn’t have to wake up at 3 a.m. wondering if we got that ad out on time, or what the headquarters was doing in Nevada, or who was saying what, or what the headline was.”

But the glee of the 2020 victory was quickly quelled by the realities of governing in an incredibly fraught era. Is it more difficult to handle the brutal barbs of politics today when the subject of them is a sibling you revere? “Joe takes a hit a lot better than I do,” Biden Owens says. “Joe is a big boy, [a] strong politician. Joe says that politics is personal, but he doesn’t take it personally. Sometimes I do,” she says. “If somebody goes after your sibling or somebody you love or a child, yeah, it bothers me, but politics is an exchange, and sometimes it’s harsh, but we’re resilient. We’ve been in this business for a while. Politics is a noble profession, and I keep reminding myself of that.”

Some days are harder than others. We’re speaking shortly after a New York Times piece detailed the dissemination of Ashley Biden’s diary by political operatives. Biden Owens is frank. They’ll get through it. That’s what they’ve always done. “Look, when you’ve lost a child to glioblastoma, a 46-year-old young man who had the world in front of him, who’s among the best human beings in the world, or when you have almost lost another child to addiction…you can handle anything,” she says.

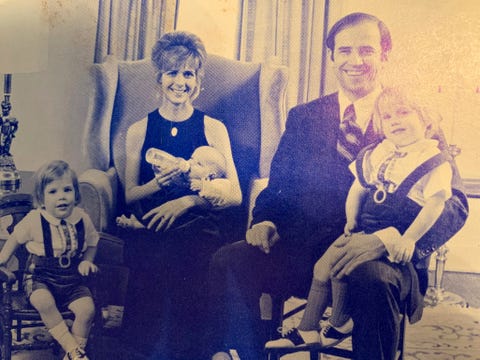

“My brother was good. He shared his boys with us.”

She isn’t referring to Beau, who died in 2015, and Hunter Biden, whose 2021 memoir Beautiful Things depicted his brutal battle with drugs and alcohol, as a typical aunt would, because, in so many ways, she is far from your typical aunt. Because she helped raise them, she considers her nephews more like her sons. “To be clear, yes, I did jump in and move in with my brother to help raise Beau and Hunt, but there was nothing heroic about it. It was the family code,” she says, of the period following the deaths of Neilia and 13-month-old Naomi. “My brother gave a tremendous gift to me and my brothers Jimmy and Frankie in that he shared the children with us.”

Biden Owens was 27 years old when she became a de facto mother to the Biden children. “I was with Joe in Washington, D.C., hiring staff, and the world turned upside down. It went off its axis,” she recalls. The accident happened the week before Christmas. A home had been purchased in the nation’s capital and the family was set to move in January. “I said, ‘Well, look, I’ll come. I’ll come in and stay until it’s time to go.’ And that’s what we did. It was a tragic time, but it was a beautiful time. It was beautiful in that it’s what family does. We came together, and we were together. We were even more together. And Beau and Hunter healed us. They healed my brother’s heart.”

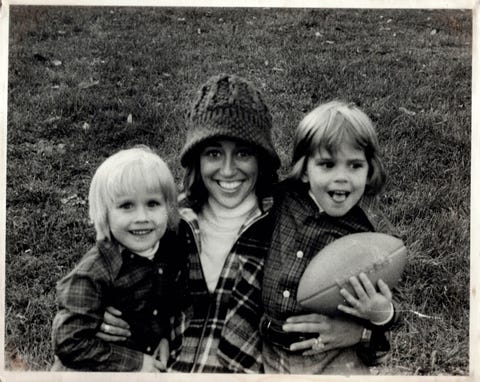

“I was by no means a born-ready mom,” she says. “I figured that someday I’d grow up and get married, and I’d have children—that’s kind of a byproduct of getting married. It was an unhappy time in my life, and the boys healed all of us. For me, they broke my heart open again to love. Joe just said this on St. Patrick’s Day—he said that courage is the greatest of all virtues because, without it, you can’t love with abandon. Well, Beau and Hunt broke open our hearts again, and we could love with abandon. Joe, within that five-year period, marrying Jill, me marrying [my husband] Jack, and then [our younger brother] Jimmy found [his wife] Sara. It was extraordinary.” She talks about taking family trips in a Jeep. To her, they were magical.

“I’m Aunt Val,” explains Biden Owens, who has three children with her husband, John T. Owens. “I remain very much in their lives. I’m pretty darn sure of that. My eldest son, my only son by birth, his name is Cuffe. When Beau passed away in 2015, the whole family was devastated. My son said to me, ‘Mommy, it’s okay. Cry. You lost your firstborn.’ So my brother was good. He shared his boys with us.”

Biden Owens brings up an oft-cited Biden line, “Faith sees best in the dark,” from Søren Kierkegaard’s Gospel of Sufferings,after I mention how my own faith was tested in the past two years—albeit to a considerably minor degree than anything she’s experienced—and that my family stepped up in such a way that I came to see my parents in a new light. Upon hearing this, Biden Owens met my words with a level of compassion that left me stunned.

“What I’ve learned, what I believe, is that adversity builds character more sharply than the spoils of victory,” she starts. “Beau died on May 30, 2015, and Pope Francis came to Washington in September of the same year. My daughter Casey and I went with Joe to the mass that he had outside the Basilica. The Pope’s homily was, ‘Keep moving forward. Moving forward.’ I thought he was speaking directly to me and my brother, because that’s what my brother has done. He gets up and keeps moving forward.”

In Growing Up Biden, Biden Owens seeks to illustrate the fundamental human elements that she believes tie a thread from the First family to all Americans. “Tragedy has struck our family, but it’s hit every American family,” she says. “We just happen to be in the public eye. It doesn’t matter what the tragedy is. People walk around with holes in their heart and tears in their heart.”

“It’s about connections and the bond,” she says. “‘Empathy’ is a fancy word, but it simply means ‘to feel.’ Not to feel as in to touch, but to feel as in absorbing the emotions of another person. To the extent that we can do that today, I think we’re better off for it.”