The Covid-19 pandemic has hit the luxury sector extremely hard, causing

a sales downturn of approximately 20% in 2020. The physical retail channel in particular has suffered, while online luxury sales have soared, strengthening the position of multibrand e-tailers - the real winners in this revolution - and of leading luxury labels, which have become even more powerful. In this context, other luxury players will have to reinvent themselves, and substantially rethink their distribution strategy, according to Luca Solca, senior luxury analyst at consulting firm Bernstein.

British site Lyst has been one of the winners as online sales have soared in the luxury market lyst.com

On Tuesday, upon the publication of the study entitled ‘Luxury retail evolution & the digital revolution’, carried out on behalf of Altagamma, the association of Italian luxury brands, Bernstein held a video conference focusing on the post-2020 status of luxury goods distribution. An analysis that is all the more necessary at a time when the barrier between offline and online sales has virtually vanished.

“These two channels are increasingly integrated, so that we can now speak of ‘onlife’ sales”, said Matteo Lunelli, president of Altagamma, referring to ‘Onlife Fashion’, a recently published book written by Giuseppe Stigliano, Riccardo Pozzoli and Philip Kotler. As Solca pointed out, “2020 saw a commercial acceleration by e-tail sales, whose share of the total [luxury] market rose from 12% in 2019 to 20-23% a year later, reaching a total revenue of €50 billion, a five-year gain for the luxury industry.” A trend that is set to continue, as online sales are expected to account for one third of the market by 2025.

From influencers to social media, e-shops and multibrand websites, a multiplicity of centrifugal forces have pushed consumers away from traditional monobrand stores. A slump of in-store traffic that was exacerbated by the Covid-19 crisis, and was only partially offset by the e-tail channel’s high conversion rates. There is a significant risk that sales per square metre will dwindle for luxury labels.

In the study, Solca demonstrated how growth in comparable sales is clearly linked to growth in return on investment. A growth that is doubly important, since it creates value, and in turn leads to stock market success for luxury groups, prompting a corresponding rise in their share prices. In short, Covid-19 and the digital acceleration have dampened down store footfall and profitability, putting further pressure on labels and forcing them to react to remain competitive.

In-store events, capsule collections, pop-up stores, ad-hoc customer services such as dedicated shop assistants or exclusive access, which generate greater added value, are ways of stemming the bleeding. But they imply additional costs that only the most powerful luxury groups are able to afford, through their scale economies. The same logic is now coming into play on the web.

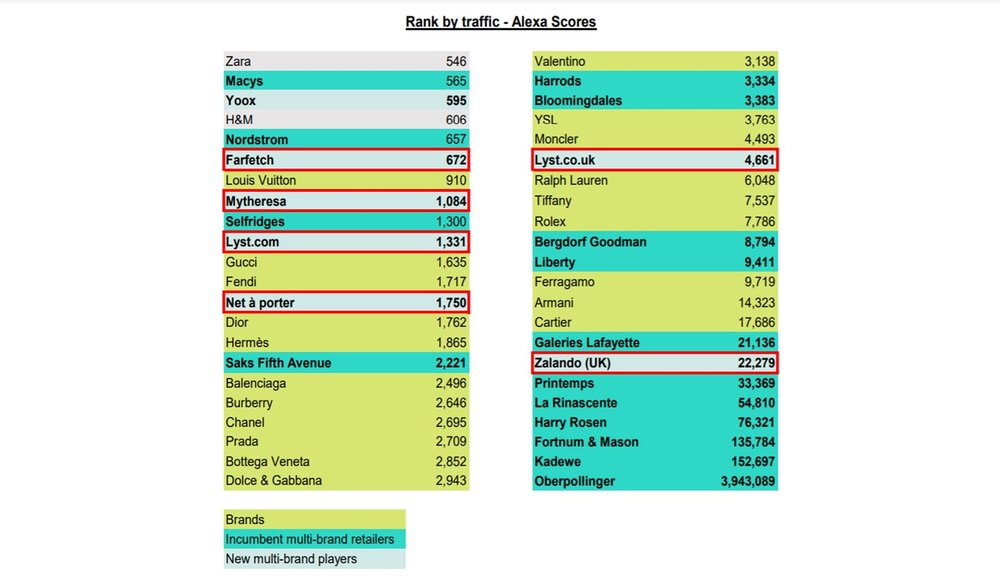

“The digital acceleration has contributed to the strengthening of multibrand e-tailers. In the online world, consumers flock to those platforms that have been able to aggregate a vast number of products and brands,” said Solca, mentioning Lyst and Farfetch, whose size is “from ten to one hundred times larger than that of their competitors.” These two e-tailers, alongside Mytheresa and Net-A-Porter, now attract more traffic than traditional department stores like Selfridges, Saks Fifth Avenue and Galeries Lafayette.

“We are the new winning proposition. The emergence of multibrand sites like ours was previously unthinkable in the retail world,” said Chris Morton, CEO and founder of Lyst, whose sales boomed in 2020, increasing by 50%. The British fashion e-tailer and search engine is now available in 200 countries, 90% of them between Europe and the USA. It claims 150 million annual buyers, 17,000 brands and 8 million products, with 100,000 new items featured on a daily basis.

“Consumers primarily forge a relationship with brands. They are on the whole rather agnostic about the various sales channels, but they are becoming increasingly accustomed to e-tail, which they use as the remote control of their lives. It is up to us to understand their needs,” said Morton.

The technological savvy and commercial fire-power of e-tailers have enabled them to consolidate their e-concession model, tapping the global inventory of the labels they feature. With this formula, the labels still own the goods, and manage deliveries directly. Unlike the classic physical retail distribution model, in which inventory used to be allocated locally to each department store branch.

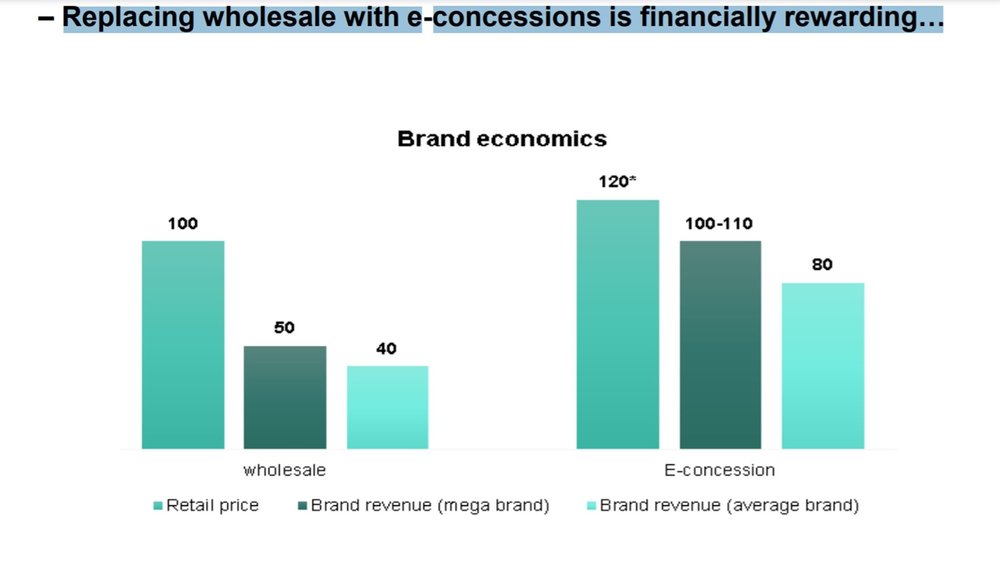

“At the same time, several labels have accelerated the streamlining of their traditional wholesale network, allowing them to place greater emphasis on multibrand e-tailers where, via e-concessions, they are able to have more control over their prices,” underlined Solca. “Another advantage for luxury labels is that, selling online, they make more money because they apply retail prices, minus the commission owed to the e-tailer, while from their usual multibrand clients they only receive 40 to 50% of the retail price.”

Solca noted that “the system works well especially for the larger labels, while for smaller ones, it translates into a further strategic disadvantage they have to take into account. Luxury houses such as Dior, Hermès and Louis Vuitton have already integrated the e-tail model into their own distribution ecosystem, and they do not always require the assistance of e-tailers. On the contrary, it is [labels such as these] that generate traffic for e-tail sites.”

“E-tail is and will remain an important element of the luxury market, but online sales will not reach such a large market share,” said Michele Norsa, executive vice-president of Salvatore Ferragamo. “There will be a geographical rebalancing, as well as a rebalancing of the various sales channels, because the in-store experience quality remains essential. We must avoid the kind of homogenisation by which we could buy anything in a few clicks,” he added.

“We have recently reopened, and we can only attest to the fact that customers are returning en masse, especially at our hair salons and starred restaurants,” said Michael Ward, managing director of the Harrods department store in London. Harrods has recorded a 15% decline in footfall since it reopened, compared to the same period pre-Covid, while in-store traffic plunged in 2020, dropping by 68%.

The numbers are indeed promising, especially since tourists are not yet back in the British capital. “What’s happening is that people are visiting us to enjoy a unique experience. They want to experience again the magic we have managed to retain,” said Ward.

But doesn’t the luxury experience also entail “the possibility of ordering a highly desirable, specific product by simply clicking on a screen, while enjoying a glass of fine wine in the comfort of one’s own living room?” asked Lyst’s boss Morton. It is a delicately balanced equation, one that luxury labels will have to try to solve in the coming months.