Virgil Abloh is the quintessential contemporary fashion designer: he knows streetwear and luxury are one and the same, and collaborates with Nike as easily as he does with Chrome Hearts. As

a public figure, he’s as well known as the products he makes, from garments labeled with quote marks to hyped-out accessories that spike his collections at Louis Vuitton.

He also likes to copy. Nearly every one of his collections, for Off-White and Louis Vuitton, includes at least one garment or idea that seems to have appeared in another fashion designer’s collection first, and that sparks active debate online. And yet his penchant for copying is arguably his most considered practice. After all, the work that first yanked him into the menswear spotlight, Pyrex Vision, was a collection of tweaked readymades—like flannels from Ralph Lauren’s Rugby line screenprinted with “PYREX” on the back.

Copying, of course, is the cardinal sin of fashion, especially in the current era. Brands zealously guard their trademarks (including Abloh, whose litigiousness may suggest that he believes his take on copying is something more considered than mere hype-chasing knockoffs). Abloh’s rise has happened in tandem with the growth of social media, which has a unique hold on fashion discourse (most of the new guard of self-appointed critics and commentators have come up on Instagram, Twitter, and Youtube). In an industry known for gatekeeping, calling out copying has made the average social media user unusually powerful. A few years ago, Pyer Moss designer Kerby-Jean Raymond told the Business of Fashion that “we are really scared to end up on Diet Prada,” which began as a platform to call out knockoffs.

But the more I’ve thought about Abloh’s work, along with that of peers like Marc Jacobs and the younger design collective behind Vaquera, the more I wonder whether copying is in fact still verboten—or whether it has become the coolest thing you can do.

More recently, Abloh has expanded his thinking on copying to embrace concepts from DJ culture, which constructs something new from pieces of other artists’ work. His ever-expanding show notes for Louis Vuitton this past July included a number of riffs and essays about sampling; the collection was called “Amen Break,” after one of DJ culture’s most commonly sampled drum breaks. One piece, a letter to “Dear Fashion People,” noted that the Amen Break has been sampled over 4,000 times, and that “the Louis Vuitton Spring-Summer 2022 Men’s Collection follows this logic of sampling the readymade to make new things from the old. Men’s Artistic Director Virgil Abloh understands how much of today’s culture has been about stretching that initial six seconds into an infinite loop.” It concluded, “Abloh’s praxis is crate-digging through the canon to find the B-sides and rarities that mustn’t be forgotten. He juxtaposes references in the same way a DJ beat matches two disparate tracks—you find the mutual point where the vibe lines up and switch it up from there, an act of coordination that takes painstaking practice to look absolutely effortless.”

When critics and commentators complain and complain and the creator doesn’t change, but instead doubles down, we have to ask: is it we who are missing the point? Knocking off isn’t a naughty habit of Abloh’s; it’s the entire purpose of his work.

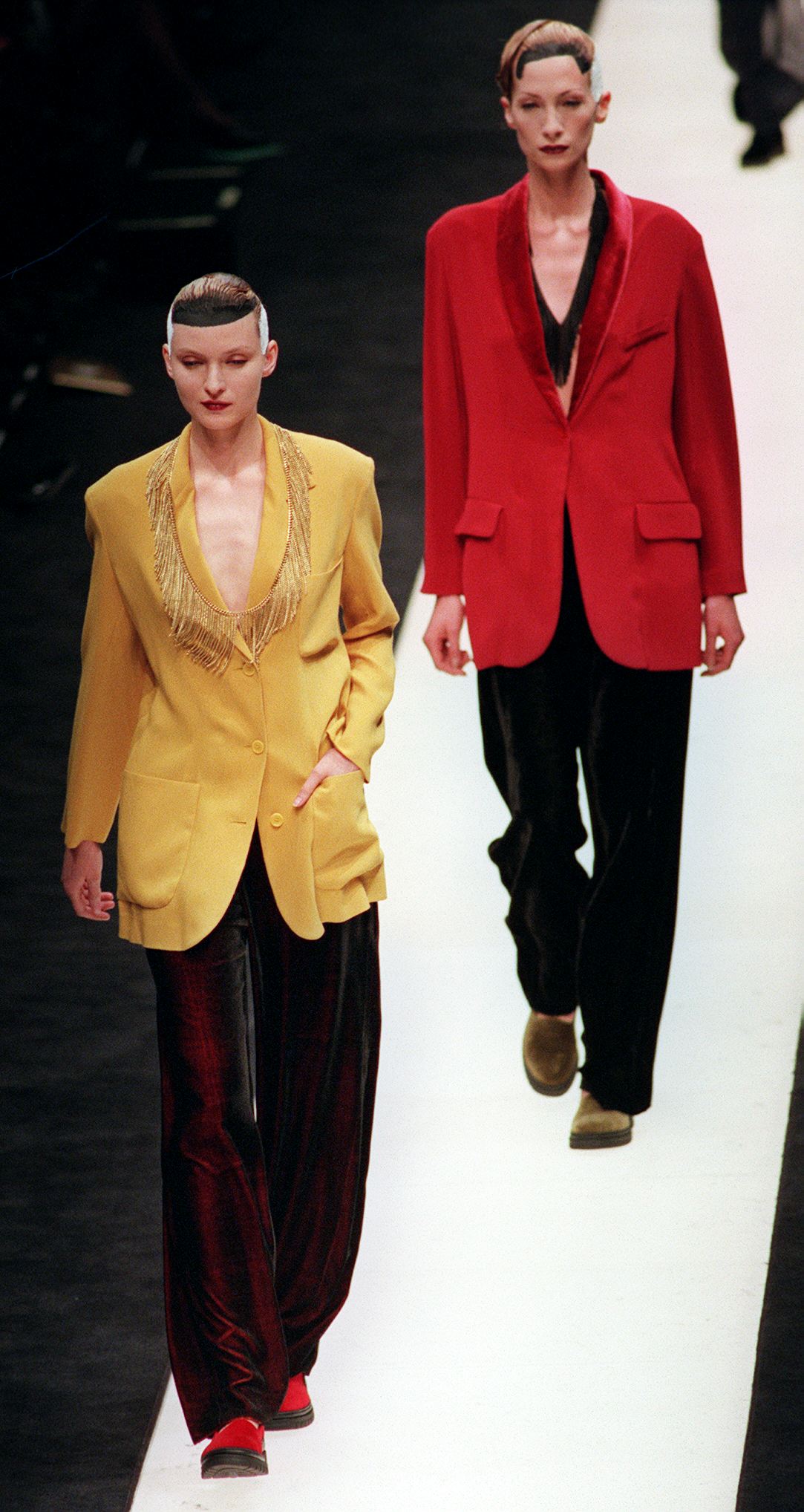

Abloh is one of the great eccentrics in fashion history, but he’s not alone in his embrace of copying. Marc Jacobs, Abloh’s predecessor of a sort at Vuitton, not to mention one of his idols, has been challenging the simplistic conversation around copying for years. Around 2018, he began to make collections that seemed almost like fashion fan fiction. He had been mistreated by the industry: his parent company seemed to have neglected him, and the New York Times ran an unflattering piece about the state of his business. In response, he began to design with a pure, almost innocent spirit, creating homages to the designers he grew up idolizing as a kid working at Charivari on the Upper West Side. He recreated Claude Montana’s huge shoulders and Yves Saint Laurent’s jewel tones, and it looked like nothing else at the time—but like many things that had come before. In the late winter of 2020, Jacobs showed a collection that was widely praised as a major career highlight. It quoted heavily from designers he admired, many of whom are in his wardrobe, from Demna Gvasalia’s Balenciaga to Alessandro Michele’s Gucci. Many looks even seemed to recreate runway photographs from Versace and Calvin Klein shows of the 1990s. A number of social media users were perplexed by the similarities between Jacobs’s garments and these images from fashion history both recent and far in the past—neglecting that Jacobs, an obsessive student of fashion (and an ardent shopper), had clearly intended the show as an homage to fashion itself, an industry-wide mood elevator that is still cited regularly by editors and commentators as a signpost for where fashion should go next. Jacobs has also made a number of Chanel-inspired jackets—perhaps inspired by the ones he owns himself. He’s like a writer who wants to feel the weight of Hemingway’s sentences by writing them out by hand—by copying, he’s conversing with the original genius, putting his modern spin or accent on something that epitomized its own moment.

“Fashion fan fiction” is a term that originated with Vaquera, the collective of twenty-something (now thirty-something) Brooklynites which emerged in the mid 2010s as an earnest, New York dreamer’s answer to the Paris-based collective Vetements. Vaquera’s designers quoted designers they loved—they even cast Andre Walker in one of their shows—and made fan T-shirts with the names of their icons like Miguel Androver. Like Jacobs’s recent collections, the mood is one of adoration, and also suggests to critics and shoppers where in the canon Vaquera hopes to belong.

Of course, there are still knockoffs that fall outside the frame of good fashion ethics. Fast fashion brands, from Shein to Fashion Nova to H&M to Zara, make replicas of designer garments intended for a knowing audience, which theoretically short shrifts the originator of the piece. It also exploits precarious labor markets, made up mostly of poorly paid women, in countries like China, India, and Bangladesh. Still, whether someone who is buying a $30 jacket would opt to buy a $800 or even $300 one if the knockoff did not exist is tough to say. The statistics suggest that fast fashion shoppers wear things only once or twice before discarding them, so it seems that the demand for fast fashion is less about broad access to good design and more about a demented appetite for a multiplicity of looks.