This past May, Keisha Lance Bottoms shocked Atlanta—and the nation—when she announced she wouldn’t be running for re-election, ending her tenure as the city’s mayor after one term. Over the years,

it’d become rare to read about Bottoms without seeing the words “rising star” attached to her name; the Democrat landed on the shortlist to be Joe Biden’s vice president and was offered a position in Biden’s cabinet. In March, Biden held his first fundraiser as president for Bottoms. But her time in office was also marked by unprecedented crisis: She faced a cyberattack against the city, a continued federal investigation into her predecessor, and a pandemic, during which Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp sued her over her mask mandate and she and her family tested positive for COVID-19. There was a summer of racial justice protests, and that June, an Atlanta police officer shot and killed 27-year-old Rayshard Brooks.Overall, Bottoms has been criticized for how she’s responded to the city’s rise in violent crime.

Still, deciding not to run for re-election is usually uncommon, especially in Atlanta.But Bottoms isn’t alone; across the country, Politico reports, there’s been an exodus of mayors after “a year like no other.”(Bottoms’ last day in office was Jan. 3.) The constant emergencies, exhaustion, and trauma have left many leaders ready for something new—or, at the very least, a break. In her own words, the former mayor describes how she navigated her term, and why she ultimately decided to walk away.

Very early on in my tenure as mayor, I was at a dinner when a neighbor, an older woman, asked me to come over. She whispered in my ear, “We kill our leaders.” I said, “What?” She said, “We tend to kill our leaders. We will expect so much of you and take so much of you that we will kill you. And when you’re gone, we will miss you. We’ll say how much we loved you.

“And then, we will move on.”

It was a very long process to decide to run for this office—much longer than a lot of people, including my husband, wanted it to be. I knew, in some way, that embarking on a run for mayor would change not just my life, but my entire family. I knew it was going to be a very grueling and difficult, and likely very ugly, process. It was not something I wanted to go into halfheartedly.

In the end, the race was as long and as difficult and as challenging—and probably even uglier—than I could have ever anticipated. The night of the runoff election, our numbers kept going back and forth, and we were essentially tied at some point. There were just a few hundred votes separating us, and when the numbers flashed on the screen, I dropped to my knees and prayed to God, “Don’t bring me this far to lose.”

Unfortunately, I didn’t get much of a honeymoon period. When I stepped into office, there was a big federal investigation into the previous administration. Three months into my term, there was the largest cyber attack in the history of any American city. Then there was COVID and the protests of 2020. My election and the campaign were just previews of what to expect from my term: non-stop crisis after crisis.

I didn’t know why, but in my first year of office, I always felt like I would only do one term. During Joe Biden’s campaign, I was being vetted for vice president, and I thought, oh okay, maybe this is why I felt that. Then we had discussions about whether or not I would join the administration, and I thought, okay maybe thisis it. But the reality is none of that came to pass, and none of that was the reason. I still don’t know why I felt that way my first year, but perhaps that’s why it wasn’t a foreign thought when the time came to decide.

I think it’d be easy for people to understand if I could put a nice, tidy bow on it and say, “This is why I didn’t run again.” But the reality is so much more complicated than that. Many people believe being the mayor of Atlanta is a dream job, and in many ways, it is. But there’s a moment to dream, and then there’s a moment where you have to wake up and move on. The reality is there was a tugging inside of me, and the hardest part was saying it out loud. I knew what I felt, but I didn’t want to disappoint people, and I felt apprehensive about doing something out of the ordinary. But once I said it, I felt a huge wave of relief and confirmation I had made the right choice. I also had to let go of the God complex—that only I could be mayor and only I could have a vision and only I could lead the city. Once I released the need to control the narrative, and the need to control the direction of our city, it was a very easy decision to make.

I knew I could run for mayor again. I knew that I could win. I knew I could do the job for another four years. But at what cost?

This past year has been referred to as the Great Resignation, but I like to call it the Great Reevaluation. People across the country, including elected leaders, are reevaluating their lives: How do I want to spend my time? How do I feel I could best make an impactful change in my community? I knew I could run for mayor again. I knew that I could win. I knew I could do the job for another four years. But at what cost? Right after I announced I wouldn’t run, several people told me my voice sounded different. That was scary—that there was a lightness in my voice they could already hear. People told me I was smiling more; I didn’t know that I hadn’t been. I asked my mom about it, and she said, “There was a heaviness in your voice.” I told her, “There was always something heavy going on.”

To our incoming mayor and to elected officials across the country, especially women, my advice is to protect your peace. Turn off sometimes. It’s difficult to do, especially when you’re the primary caregiver. When you have children in your house, you work all day and then go home and do a different kind of work. And in a job like being mayor, you’re already working 24/7. There were so many times I wish I did not have to watch the news or read the paper, but I had to. I had to consume it all every day. The last two years, having to consume all that we’ve faced—it’s a lot.

There was an office next to mine that I called the Happy Room, a physical space where we were only supposed to talk about good things. That was necessary, to be able to separate the heaviness from the lighter moments. But the past few years, there hasn’t been the balance you would hope for—not that anybody signs up for the job because they just want to be happy. That’s not why you run. And not that I was unhappy all the time, but over the past few years, it certainly could feel that way.

There were moments when I felt that I was suffering from mild depression, but it was a very depressing time across the globe. There were times I felt very anxious, but there’s been a lot to be anxious about. I saw an interview with First Lady Michelle Obama where she said she was low-grade depressed, and I had used those exact words with my husband two days before. When I saw she said that, I thought, okay, there are other people feeling this way. But one of the most disturbing things I experienced was, at certain moments, feeling like I lost the ability to empathize and sympathize. When you’re facing challenge after challenge, and in some ways trauma, you probably put up a shield and armor to protect yourself. That was a moment for me to stop and make sure I was okay and healthy and whole.

I also know that if I want to be able to give my best self, it’s time to put a period at the end of this season.

It’s incumbent upon officials to try and preserve whatever peace they can in whatever way they can. But it’s also incumbent upon the public: If you want good people to continue to run, to serve in office, and to step up and lead, the public has to be more understanding and forgiving in terms of the humanity we all need to protect in order to be our best selves.

As for what’s next, I don’t know if I’ll ever run for office again or serve in a public capacity. I enjoyed making a difference in the lives of people across our city, and I don’t think that passion and desire will go away. But I also know that if I want to be able to give my best self, it’s time to put a period at the end of this season.

This past year, I’ve cheered on women like Simone Biles and Naomi Osaka who chose to take a step back. It was the bravest, most courageous thing any person can do, and to see them do it at their age sets the expectation for so many others. As women, we often don’t stop to adjust the “S” on our chest. We think we’ve got to keep flying through, because that’s what’s expected of us, especially women of color. There’s this historical perspective that we can withstand anything, and in many ways we are strong women, but we’re also human. And we feel the pressure not to disappoint, because we are representing not just ourselves, but in many ways, communities and an entire race of people.

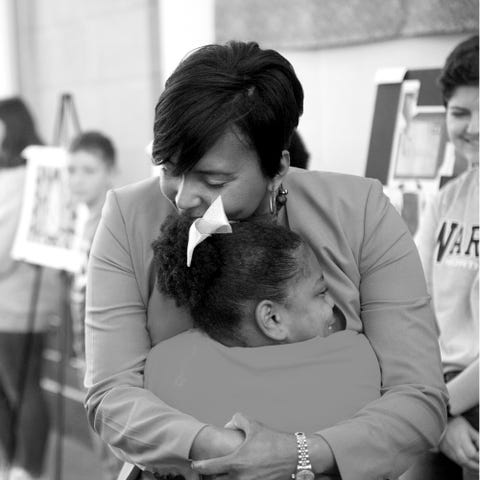

My prayer now is to find that same purpose and passion I found in serving as an elected official. This Thanksgiving, one of my cousins was looking at this picture my mom has on her wall: It’s the front page of the newspaper the day I was sworn in. He looked at it and said, “Look at your face and your eyes, so full of hope.” That’s what I want to find on my next journey, that same evident hope.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.