No one would guess their value. A recipe scribbled in pencil. A cow-shaped potholder. A blue-glazed ceramic pie plate. Seemingly innocuous items from the kitchens of my mother and stepmother. My

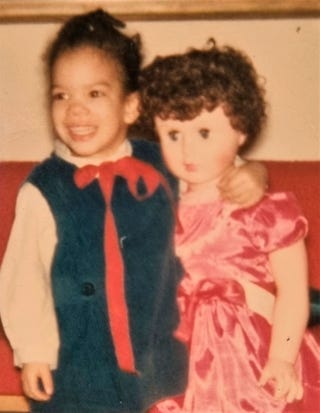

two mothers. The women who took turns raising me in different periods of my childhood in their blended households.

My mothers’ upbringings could not have been more different, though sometimes they seemed similar in the telling. Small-town Jamaica versus small-city New England. Parents lost, dreams given up, some wishes fulfilled. Both formed families with men from other cultures. Both are gone now, but they live on, in part, through the workaday keepsakes whose value no one would guess.

The ceramic plate makes me think of fruit pies, and summer barbecues, and autumn leaf-raking parties amid the burnished red of fallen maple leaves. The kitschy potholder with its imitation-quilt cow makes me smile. The mother who gave it to me never liked it, but I did. It had belonged to a beloved aunt, and by giving it to me, she’d kept it in the family. The recipe, written on lined notebook paper by my other mother, did more than bring back memories. It eventually stepped off the page and worked its way into the broad landscape of my imagination, inspiring the title of my debut novel, Black Cake.

The recipe includes instructions for making a rum-soaked fruitcake, or black cake, as many Caribbeans would call it. When a younger relative texted me to ask for the recipe, it started me thinking about inheritance and how we choose to keep some things closer to our hearts than others—especially in a multicultural family like mine.

We know that food helps to build connections between people. But people migrate, marriages break up, people remarry, strangers move in together. Food can also play a role in anchoring individuals, families, and entire cultures amid change. Sharing a family recipe can carry the same weight as sharing a piece of heirloom jewelry or an ancestral home. Especially if a recipe, a language all its own, is all a person has left to give.

In my novel, the traditional Caribbean fruitcake symbolizes family bonds and memories in the face of significant loss, but also a multicultural history. Black cake is a descendant of the English plum pudding, but has evolved over time into something unique and more tropical in the blend of its key ingredients. It is the quintessential Caribbean cake for celebrations. It makes me think of holidays and weddings. It is a source of joy. But also, it is the offshoot of a less-than-sanguine past.

The recipe for black cake serves as a reminder of the ways in which we gloss over the complicated stories behind certain beloved foods, from the famed Mediterranean diet (which exalts the tomato that came from South America) to the sometimes-tortuous history of sugar and rum (whose presence in Western diets and economies was propelled, early on, by colonialism and forced labor).

In families, too, nostalgia can give way to the kinds of stories that people would prefer not to tell. Like my own mothers’ memories of abandonment, miscarriage, or the true cause of a loved one’s death. Many families have stories like these, and when they finally emerge, they often do so in the kitchen, at the table, over a meal, or with a glass in hand. Sometimes, enough years have gone by that such stories become a source of mirth, like my long-sober uncle’s occasional “when I was drinking” stories. He always had us in stitches.

Or, as in the case of the matriarch in Black Cake, some people reveal nothing until after they’re gone.

My novel is not autobiographical, but the emotional currents that run through any work of fiction often link back to real-life emotions we have experienced, or heard about, or read of. I have no recollection of my mother and father living together before their divorce. I only recall them arguing later, over long-distance telephone lines, year after year. But I almost always remember my stepparents being part of my life. Part of my shape-shifting sense of family and home.

Together, the two couples who called themselves my parents formed a loose clan of ruptures and alliances. Together, and despite all, they were part of a greater, though somewhat bruised, whole. Those old kitchen items aren’t the only things I’ve kept from my parents. But it may very well be their domestic, ordinary nature that has wedged them so solidly into my emotional genome. They keep me anchored to a sense of having come from somewhere and belonged to someone. One’s sense of family and home may shift over time, but it remains embedded in our hearts and our sense of self wherever we go.

Black Cake (Ballantine Books) is out on February 1; a series based on the book is coming to Hulu.

This article appears in the February 2022 issue of ELLE.