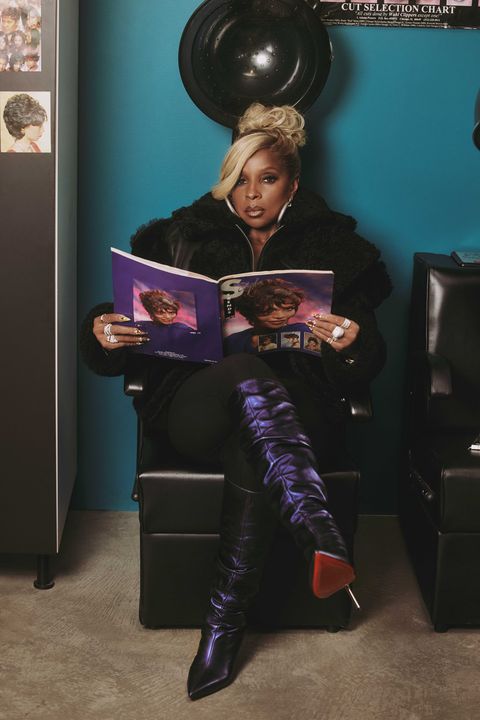

It is clear even before Mary J. Blige appears for her cover shoot on a balmy Thursday morning in Brooklyn that the singer is her own weather event. A gust of nerves and angst passes through the airy salon. Not even 100 percent of the correct vibes—glowy mirrors, purple patent swivel chairs with the sheen of hard candy, and walls bedecked with fellow icons like Macy Gray and Lil’ Kim—can assuage the jittery crew. In the back of the salon, the singer’s go-to stylist, Jason Rembert, is reviewing a rack of clothing pulled for the photoshoot, caressing a yellow-and-black-printed puffer coat. The bustling ceases when Blige’s car pulls up to the front, everyone standing still in their spots as if Queen Elizabeth’s carriage were making its way down the Brooklyn street.

The Queen of Hip-Hop Soul emerges from her Range Rover wearing her signature “ghetto fabulous” style: a logo-heavy Gucci bucket hat, cropped leather jacket, shorts, matching thigh-high Gucci GG monogram boots, and chains—lots of them. She flashes a nervous smile to the chorus of workers standing on the sidewalk and heads to her glam trailer to prepare for look one: a sumptuous floor-length, espresso-brown faux-fur coat.

Under the blinding LED lights ringing the salon, Blige looks relaxed—a legend can make the most of even a makeshift spotlight. So it may come as a surprise that Blige’s own sense of beauty has been hard-won. “I didn’t feel beautiful—like for real for real, not just ‘Hey, I’m pretty’ but actually believing it—until about 2016,” Blige tells me. The nine-time Grammy Award winner has been in the spotlight since at least 1992, when she released her debut album, What’s the 411?—meaning she’s performed, acted, and been the unwitting subject of paparazzi photos for the better part of her adult life, all while feeling uncomfortable in her own skin. She attributes her discomfort to a mix of insecurities, including a childhood scar under her left eye and a tumultuous 13- year marriage to her ex-husband and former manager. “If you’ve been beat down mentally by someone, you’re never pretty enough. You’re never smart enough. Nothing’s ever good enough,” she explains.

Blige’s journey to beauty acceptance has been a long one. As a teenager, she was sitting watching television in the Schlobohm housing projects in Yonkers when Salt-N-Pepa’s “Shake Your Thang” video came on. Blige’s gaze drifted to their intricate blonde asymmetrical cuts. “When I saw Salt’s hair was platinum, it was done. Game over,” Blige says.

Before Salt-N-Pepa added some seasoning to her life, Blige struggled with her hair. She felt its sandy brown color blended into her skin, leaving her hair looking flat and without character. “It felt like cotton,” she says now. “My mother pressed it, and she put all these ponytails in it. It looked nice when she pressed it, but when it was kinky, it just looked nuts.” She felt like an outlier at school. “Because of the texture, growing up I always wished I had wavy hair. Every little Black girl wanted wavy hair.” For a while, she resorted to perms, weaves, and dyes to give her hair the dimension she felt it was lacking. Identity meant everything to young Blige. “That’s what was cool about the hood—everybody had an identity. Nobody wanted to look like the next person. Nobody was trying to duplicate anybody,” she says. And nobody in her circle had been bold enough to try blonde hair—yet.

But in high school, with some help from Salt-N-Pepa, Blige found the look that would become her hallmark. “I used peroxide to lift my hair color all the way up to platinum [blonde],” she remembers fondly. Blige developed a knack for experimenting with different hair colors and styles, from blondes to reds. Society has always tried to police Black women on which hairstyles are deemed acceptable or which lipstick shades are flattering. Blige’s platinum blonde was the middle finger to old-fashioned hair stereotypes set in place to push Black women away from the center of beauty conversations. Blige was the disrupter.

As a Black teenager growing up in the Bronx—not far from Blige’s home zip code in Yonkers—I came of age in the kind of salon we’re shooting photos in. The salon was a microcosm of Black womanhood, a place to try on looks society (and our mothers) had steered us away from. I learned there were “safe” hair color groups: Maroon burgundy was a daring color, but anything veering closer to fiery red was dismissed as “ghetto” or “loud” by older women in my orbit. Blonde was never a thought for me growing up. No matter how attainable Blige made blonde hair seem for Black women, my deep skin and fear of damaging my strands made me look the other way. Blonde was a color relegated to “bombshells,” with an image search history excluding Black faces. So I opted for a gingery brown, dyeing just the ends for my initial color job, and then gradually moving up to streaks as my confidence strengthened.

That’s the thing about Black hair—it’s not just something to fiddle with. Our hair holds emotional significance and helps define our identity, especially when the societal standards of what constitutes “beautiful” rarely include Black women who look like Blige. It took a few dye jobs to finally find myself. My mother found her look in reddish browns; I found mine years later in aquamarine blue. Blige found hers in blonde. She was subtly championing radical self-expression by borrowing references from the past, reimagining them, and making them her own, with immense impact on fans and fellow musicians alike.

The hood loved the blonde look, but the music industry she entered at a mere 18, when she signed to Andre Harrell’s Uptown Records in 1989, thought the look was too rough. Blige maintains that she wasn’t trying to make a statement. “When I got in the business, I was already blonde. I was already red. I was already doing those colors. I wasn’t searching for an image. I was my own image,” she says. At the time, the sultry, feminine aesthetic of popular soulful crooners like Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey matched the emotive ballads that catapulted them to fame. Blige, on the other hand, was not that person.

Blige emerged on the scene with What’s the 411? showing off a shaggy chocolate-brown bob, dressed in baggy clothing and sneakers. This tomboy sartorial slant was rooted in survival, not aesthetics. “When you have a single mother with two little girls living in the hood, you develop tomboy skills. You become the guys you’re hanging with, but I’m still a girl. I’m a little rougher because my environment is rougher. There’s always something you have to fight for. It was never a comfortable situation for little girls, so we had to be little tomboys to get through that time of our lives. By the time I got into the music business, that’s exactly what I was,” she says. She never desired to conform to society’s vision of what an R&B singer is supposed to look like. “I was sitting on the shelf because they didn’t know what to do with me, because I was not going to put on a gown,” she says.

Music was her first language, but fashion was undoubtedly her second. The singer turned the notion “sex sells” on its head by settling into a Yonkers-inspired wardrobe of oversize jerseys and tennis skirts, backward baseball caps, and Armani suits while pleading her case for love on vinyl. With the help of renowned stylist Misa Hylton—who also made her name dressing Jodeci and Lil’ Kim—Blige popularized the movement called “ghetto fabulous”: aspirational glamour marked by gaudy displays of wealth, like furs, jewelry, and logo-heavy prints. In other words, dressing extra AF.

While music videos helped inform Blige’s idea of beauty, it was the drug dealers and their girlfriends from her old neighborhood who became another building block in her Black beauty formula. “Ghetto fabulous is just, when you come from the hood, you at your flyest. What can you afford? What can you do with it? You want stones on your nails. You want mad colors on your nails. You want colorful furs. You want Timberland boots to rock with your furs. You want a hockey jersey? It’s whatever you feel you can do with whatever you can afford,” Blige explains. “Growing up around drug dealers and the women that I hung out with, they wore furs—long sables and silver foxes and red lipstick. They were just fly. Men wore them, but when you saw a woman show up in one, you knew who she was.”

So when Blige entered the music industry and was afforded a sizable wardrobe budget, she was able to attain the markers of status she once only dreamed about. “I went for the gusto. I did a lime green sable.” The blonde hair, the gusto, and the sable were all stops on Blige’s journey to truly feel beautiful.

But the only way to get to that feeling, she ultimately found, was to let all those markers go.

For her role in Dee Rees’s 2017 historical drama Mudbound, Blige had to abandon the fluttery lashes, nix the lengthy acrylic nails, and trade her famous blonde bob for a bun. For one particular scene about 17 minutes into the film, the camera lingered for the first time on Blige’s Florence Jackson—the wife of a sharecropper in Mississippi and mother to a daughter and three sons. She appeared clad in a plain oxblood dress with her natural black hair tucked under a brown basket hat, eyes closed, with a streak of sunlight kissing half of her face. After questioning her appearance for decades, Blige saw in Florence what she hadn’t seen in herself: beauty.

“When I shot Mudbound, I was at my point of no real confidence,” she admits. Compliments from everyone on set helped build her self-image and forced her to readdress herself correctly. Every morning she would tell herself, “ ‘This chick is beautiful,’ ” she says. “So I started to believe it and started to pay myself high compliments to get past that feeling and that fear.” It was Florence who made Blige realize wigs, weaves, and makeup were just secondaries, and gave her the confidence to embrace the natural side of the Queen of Hip-Hop Soul.

Am I going to quit? No, I’m going to go to the next level.

A conversation with Blige somehow feels more unguarded than the anguished, diaristic songs of heartbreak, love, loss (and hateration in the dancery) she’s fed the brokenhearted for years. A few weeks after the salon shoot, lounging in the sunny foyer of her New Jersey home, she speaks openly of dark years of strife and insecurity. Reinvention, she says, has been her coping mechanism for escaping “hell.” “It’s not just the hairstyles and the clothing and the skin. It’s how I reinvent myself through trials and perseverance. Am I going to quit? No, I’m going to go to the next level. It’s painful to go to the next level because change is hard. But people see me come out and they think, ‘It’s just her skin or her hair.’ No, it’s her. It’s me. I’m really choosing to be a better, stronger person,” she says. The looks are just a bonus. “I won’t say hair gave me strength. I’d say I give my hair strength. Whatever I’m wearing, I’m able to have the strength to carry it now, which I was not able to have in the last layer of my life. Hair is beautiful, but I can’t carry it with confidence if I’m not confident. Because then it’d just be a weave, or it’d just be blonde hair, or my [natural] hair.”

That confidence will be essential come February, when Blige is set to perform at the Pepsi Super Bowl LVI Halftime Show alongside Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Eminem, and Kendrick Lamar. The all-star lineup of hip-hop heavyweights is also a tour through the genre’s history. You can’t talk hip-hop without mentioning the Queen.

“Hip-hop is East Coast. Hip-hop is West Coast,” Blige says. “Hip-hop is Europe—this is why it’s going to be so major, because this is what the Super Bowl is showing to people: It’s not just one thing. [Hip-hop] is everywhere.” Sharing the stage with four other entertainers means Blige will have to shave her discography down to just one song. She’s leaning toward her seminal hit “Family Affair.” The song is a favorite of Dr. Dre, who produced it. Also, Blige says, hip-hop is something of a “Family Affair” in today’s culture: “We are the culture; [hip-hop artists] give people a way to speak. We give people a way to walk. We give people a way to talk. We give people a way to think. That’s what hip-hop and hip-hop soul have done for our culture since [the beginning].”

“It’s like getting an Oscar nomination,” she says of performing on the Super Bowl stage. (Blige has two of those, actually, for Best Supporting Actress and Best Original Song for Mudbound.) Back in 2001, Blige joined the iconic halftime mash-up of Aerosmith, *NSYNC, Britney Spears, and Nelly, but sang only a few words as a “background piece” in the rock ’n’ roll spectacle. “This time I’m going to be front and center—Mary J. Blige, in her glory and greatness and swagger,” she says. And, hopefully, thigh-high boots.

Unity is also a theme on Blige’s upcoming album Good Morning Gorgeous (out February 11, pre-order here), which finds her juxtaposing new-school, trap-laden hip-hop beats with the timeless, soulful ballads that led a legion of wounded hearts to her. The album’s title track sounds a lot like the tête-àtête Blige has with herself each morning: She reminds herself she is beautiful despite the trials she’s had to endure. The song is inspired by the conversations she had with herself while shooting Mudbound.

“During Mudbound and when I was married, I was feeling so low. I had to pay myself the highest compliments, even if I didn’t believe it, just so I could build myself up,” Blige says. “I would do it in the morning, because that’s the time when your hair is not done and you don’t have on makeup. You’re just kind of dealing with yourself for real.” She still wakes up and recites the same words: “Good morning, Gorgeous. I love you. I got you. I need you.”

Styled by Jason Rembert; Hair by Tym Wallace for Mastermind Management Group; Makeup by Porsche Cooper for La Mer; Set design by Jenny Correa; Produced by Sameet Sharma.

This article appears in the February 2022 issue of ELLE.