It’s past closing time at Hemster, a buzzy tailoring start-up in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, and as the sun sets outside the industrial windows, tailors and patternmakers store spools of thread and put away irons. Inside a conference room, two women, heads bent over their laptops, are still working. One is Ann Lai, a venture capitalist who’s on Hemster’s board, and the other is its founder and CEO, Allison Lee. They talk at a rat-a-tat pace, so fast it’s like they’re getting graded on a decision-per-minute metric. The best layout for the new factory? That one. How to roll out Hemster at a big retail chain store? Like this. How can we segment customers? Here’s how. It all comes down to this: how to make something as touchy-feely, as individualistic, as tailoring into a data set that can be modeled and mined to analyze what customers might spend and how to capture their loyalty. That’s Lai’s specialty, though for several years, effectively barred from working in the venture capital industry, she couldn’t get a job doing it.

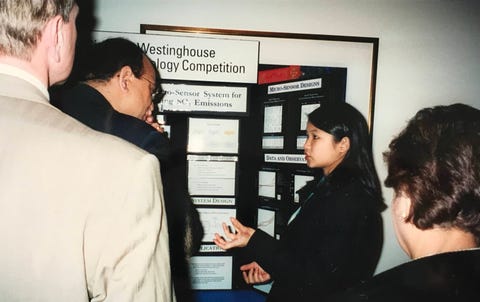

Lai was so good at science and math that in high school, she won international science fairs, worked in a graduate lab, and filed a patent stemming from her research. She went on to Harvard, where she got her bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD. After completing her PhD in 2009, she worked in data analytics and growth, then joined Binary Capital, a San Francisco Bay Area venture capital (VC) firm focused on next-hot-thing consumer companies like Snapchat. Lai joined the firm hoping she could use data to level the notoriously lopsided VC playing field, so that all sorts of founders could be evaluated for investments rather than just the bro-boys’ network. But over time, Lai bristled at how the firm’s partners treated and spoke about women, as she later claimed in a lawsuit against Binary and its two founding partners (the suit was ultimately settled, with all defendants denying liability). And so although she didn’t have another job lined up, she quit Binary in 2016 after nearly a year and a half at the firm, telling the partners why. “I was like, ‘I can’t be in a place that makes money for guys like this,’” Lai says.

“Is that your narrative?” one of Binary’s two founding partners, Justin Caldbeck, asked when she told him she was quitting, according to Lai’s lawsuit, which was filed about a year after she resigned. “If you want to leave Binary, I’ll make it happen and make sure you have no narrative.” Lai, who’d been working in Silicon Valley since 2013, knew how few women got big jobs there, how overwhelming the fratty culture was, and how often the women who spoke up about sexist treatment ended up disappearing from the industry altogether. As a child of immigrants who helped support her parents, she didn’t have the networks or money others had to fall back on.

Still, when Caldbeck said she had no narrative, she didn’t fully understand what he meant. Before long, she figured it out: When she’d joined Binary, she’d signed an employment agreement that included a non-disparagement clause. That meant she couldn’t say why she quit. She couldn’t even say that she quit. Most importantly, she wouldn’t be able to speak about Binary and the venture capital industry that had quietly overlooked the behavior that had prompted her to leave. Caldbeck was right: Legally, she had no narrative. So she set out to seize it back.

Those picturing a venture capitalist as a gray-suited executive would be hard-pressed to pick Lai from a crowd. She’s a petite 5’2” with waist-length black hair. One day she meets with portfolio companies in a floaty floral dress and chunky boots; the next, in an oversize striped oxford shirt and miniskirt with neon-green heels. (One way to be sure it’s Lai: She almost always has a can of La Colombe extra-caffeinated cold brew glued to her hand.)

Lai moved to the Cleveland area from Taiwan as a kid, learning the English alphabet on the plane over. Her father, a professor at National Taiwan University, stayed behind, commuting to Cleveland during school breaks and vacations, while her mom taught Chinese language and math at a community college. Her father’s professor salary translated into dollars wasn’t high. Often Lai, her mom, and her brother Alec would split a single Arby’s meal to save money.

She got a scholarship to attend an elite private school, and then she found out the school didn’t have resources for serious scientific research. But through her science adviser, she met a chemical and biomolecular engineering professor at Case Western Reserve University and wound up conducting research on sulfur dioxide sensors in his lab, winning prestigious science prizes. “She actually filed a U.S. patent based on her research,” the professor, C. C. Liu, said—unusual even for a grad student, but almost unheard-of for a high schooler. Lai was also a violinist, playing in the Cleveland Institute of Music’s preparatory orchestra, and made mixed-media art installations for class projects at school. She was even a hand model for an Allstate insurance ad at age 16. (And no, she hardly sleeps, hence all the La Colombe.)

Some of her drive came from interest, and some from competitiveness, but Lai also calculated that if she worked hard enough, she could get into Harvard, even as the daughter of immigrants with little pull. “Even though the system isn’t super fair, if you are exceptional enough, then it can’t mess with you,” she says. Her plan worked. At Harvard, she completed a joint bachelor’s in chemistry and physics and a master’s in applied math in four years, then earned her PhD in engineering sciences, focusing on fluid mechanics and mathematical modeling, all the while sending money home via part-time jobs (transcribing, working at a frame store).

After several data-focused growth and analytics jobs in finance and at tech companies, she joined a start-up called StyleSeat in 2014 via an introduction from a venture capitalist named Justin Caldbeck. Caldbeck was a thirtysomething investor and former Duke basketball player, Harvard MBA, and McKinsey & Company consultant who was on the start-up’s board. Lai tells ELLE she thought he could be influential in her career. Soon after she started, she says she got unwelcome late-night texts from Caldbeck. (When reached for comment, Caldbeck acknowledged the texts were “inappropriate” but claimed they were part of a mutual exchange.)

Lai says she typed vague replies and looked for a new job, meeting with VCs in hopes of moving over to the investment side. As it turned out, Caldbeck was starting his own fund, Binary Capital, with Jonathan Teo, another Silicon Valley investor, and Lai decided to work there, thinking she could “crank it out for a year or two, make my own network, and then get out,” she says. Caldbeck was getting married, and she hoped things would change. So Lai started her job as Binary’s research director in January 2015, signing the boilerplate employment agreement without much thought.

Where to start: There was the search for a receptionist, during which Caldbeck and Teo looked up social media profiles to determine the “relative ‘hotness’ ” of applicants, according to Lai’s complaint. There was the retreat where Caldbeck and Teo talked about designing an Uber-esque app to match people with sex workers, per the complaint, and the women founders pitching for investments whom the duo labeled as “cute” or too pretty—or who they said should lose weight rather than focus on the plus-size market. (Binary, Caldbeck, and Teo denied the allegations in court filings, and in Binary’s response, the company said Lai presented “an array of falsehoods and fabrications” in her complaint.)

Lai had spent high school navigating the largely male science-fair circuit and had coxed men’s crew at Harvard, and had no problem speaking up. Teo and Caldbeck quickly nicknamed her “HR,” as in “Here comes HR,” according to her complaint. (Caldbeck doesn’t recall hearing anyone use that nickname.) She threatened to quit 10 months in, but Caldbeck talked her into staying. Lai thought she’d be blackballed from jobs at different firms if the Binary partners didn’t support her leaving. She got by, until she found out that “Caldbeck began an affair with a female employee,” according to her complaint, who “showed Lai certain text messages and sought advice on how to end her relationship with Caldbeck.” (Caldbeck denies the affair.)

When Lai began to make plans to leave Binary and met with other people in the industry, she “learned additional and disturbing information about Caldbeck’s treatment of women,” the complaint says. She also learned he’d been removed from the board of a start-up, Stitch Fix, after its founder complained of his behavior, a situation Caldbeck discussed in emails Teo later submitted to a court in a 2019 lawsuit Caldbeck brought against Teo, centered on Caldbeck’s treatment after he resigned from Binary; the lawsuit was settled.

“Everyone was covering for everyone.”

Lai was dumbfounded—Caldbeck’s behavior seemed to be an open secret in tech, yet he still held a powerful position. “Everyone was covering for everyone,” Lai says. If she publicly called out Caldbeck, Lai thought it would devolve into he-said, she-said. A sexual-harassment or gender-discrimination claim would be tough, as he wasn’t harassing her, and those claims didn’t tend to go well for women. Maybe, Lai thought, if she quit abruptly, the investors and entrepreneurs she worked closely with would scrutinize the firm: She could save her career, but Caldbeck would get his due.

So she formally resigned, citing, in an email to the partners, the “hostile work environment where I do not feel comfortable in continuing to work,” her complaint said. (Binary, in court papers, said she “inadequately performed” her duties and Binary “was prepared to terminate her,” despite her claim “that she resigned as a result of alleged sexism.”)

In her suit, Lai alleged that an hour and a half after she resigned, Caldbeck texted her, warning her not to do “external messaging”—that is, discuss her departure—until “legal feedback is consolidated,” he wrote, according to court documents. Lai didn’t respond, but set up meetings with other VC firms in order to get a new job, and asked some of the Binary portfolio companies she’d worked with if they’d like her to consult for them. She soon heard from Caldbeck again, this time using Confide, a disappearing-texts app. “Stay the fuck away from our team Ann…. I’m not going to warn you again.… It’s a small world Ann,” he wrote, naming a partner from a VC firm that Lai had scheduled a meeting with. “Stop.”

Lai wrote in a Facebook post that she’d pulled “the trigger last Friday. It’s weird being unemployed, but I feel that the me that got lost along the way is coming back with every minute.” According to her complaint, more texts from Caldbeck followed. “You do understand the implications of implying that you quit unprovoked in a public setting right?” Three minutes after: “Implying that you quit because Binary Capital forced you to compromise your ethics is a clear violation of your employment agreement.” One minute later: “Please please stop making this so difficult for you.” Lai had been careful not to lie, or even say anything negative about Caldbeck or about the company, in the post. It didn’t seem to matter. And the fallout was just beginning.

Lai tried to line up work, contacting executives and VCs she knew, but promising starts led to disappearing acts. Because of the Binary situation, “it might get complicated,” one said. Another wrote, “Given the series of events there is some hesitation to have you move forward with this.” The same day, according to her complaint, Lai received a text from Caldbeck alleging she’d made disparaging comments: “These are violations of your contract and have material damages attached to them,” he wrote.

She’d later learn that Caldbeck had emailed a limited partner that they had “received complaints from several portfolio companies” about her work, according to her lawsuit. In at least one instance, the latter was partly true. Binary, in a subsequent court filing, quoted a portfolio company CEO saying “right now she simply isn’t” useful. Other examples, though, show Lai doing well. She was given a higher title and a raise. And Lee Mayer, CEO of interior design company Havenly, tells ELLE that Caldbeck had described Lai as “super smart, super talented, super analytical” and a reason to pick Binary. It didn’t seem to matter, Lai says. “[Caldbeck] said I was never going to work. And he was proving that he was taking action against it.”

Without work, Lai found her money problems were mounting. She hadn’t received her “carry,” a payment akin to a commission that’s a cut of the fund’s profits—worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. She kept meeting with new companies, but Caldbeck was “defaming her, threatening her,” according to her complaint, and “every time I would have conversations, he’d be like, ‘I heard you got lunch with blah, blah, blah.’ ‘Are you meeting with so-and-so?’” Lai says. “After that, the person I had met with would disappear.” Worried about amplifying Caldbeck’s retaliation, Lai didn’t talk about her situation even with her younger brother, who had noticed his sister seemed stressed and glued to her phone. She continued to send what little money remained in regular payments to her parents, who were saving up for a retirement condo in Taiwan, so they wouldn’t worry.

In June 2016, one month after she quit, Lai contacted a lawyer, who sent a cease and desist letter to Binary, instructing the partners to stop contacting people whom Lai might work with, and—in an instruction meant for Caldbeck—to stop contacting Lai, according to court documents. The partners responded with a bombshell: Since she’d consented to a non-disparagement agreement when she joined Binary, that meant they could not only sue Lai if she said anything that Binary considered disparaging, they warned, but also withhold much of her carry. The industry-wide sexism that she thought she’d be able to fight against? She couldn’t say a thing about any of it.

“He said I was never going to work. And he was proving that he was taking action.”

Lai decided that a backpacking trip could help with her anxiety, and got a ticket to Southeast Asia. When she left for the trip in summer 2016, she was spinning through options: go back to Wall Street, teach. Returning two months later, she decided she wouldn’t be pushed from the tech industry. “My back is already against the wall,” she says she thought at the time. “If I can’t work, everyone should know the real reason why.”

Forget the cease and desist, she told her lawyer. She wanted to do something that would actually change things: She wanted to fight that non-disparagement clause. She and her lawyer prepared claims against Binary under a California law that lets mistreated employees bring working-condition suits, meant to ensure that not only could she speak about what went on there, but other people in the industry would not be constrained by similar contracts guaranteeing their silence.

Hoping to find a job outside Silicon Valley, Lai moved to New York in fall 2016, advising companies on data, growth, and fundraising. Caldbeck sent her “threatening communications, even after being instructed by Lai’s counsel to only contact Lai through her attorney,” her complaint says, and occasionally checked her LinkedIn profile.

With no VC job offers, in January 2017 Lai accepted a position at Facebook that she felt she was overqualified for, but it provided a salary. Plus, given the company’s massive size, Caldbeck “can’t blacklist me at Facebook,” she remembers thinking. She was careful not to list the job on LinkedIn. When she returned to San Francisco, Lai threw a small housewarming party, where she thought she was among friends, and talked about quitting Binary. The next day, according to court documents, Caldbeck’s texts started again. He knew, he wrote, “that you are back in SF and my wife and I have heard what you’ve been saying to others.” “I just want to talk please.” “Can I call you?” “We are not currently suing you.” “Can you just provide a response?” “Can we just talk it through so you don’t feel like we’re out to ruin your career and we don’t feel like you are pushing us to sue you?” “Mailbox is full so I cannot leave a vm” “Btw congrats on the Facebook job.”

In April 2017, Lai met with a reporter from The Information, a tech news site, to discuss gender diversity in VC. During the meeting, Lai learned the publication was researching Caldbeck’s inappropriate behavior with female founders. She decided to wait until the article’s publication to file her lawsuit, as she knew female entrepreneurs were going on the record for the story and risking their careers. “If I can back up [what they say] with this, then they’re not going to go on record and get fucked,” she recalls.

Also in April, according to her complaint, Caldbeck texted Lai again: “Ann, I do not think talking to the information is a good idea.” “What are you talking about?” she asked. Though she knew the story was coming, she wasn’t participating. Five days later, in the afternoon: “Stop.” That evening, a single period: “.”

“The biggest thing I always told my lawyer is we’re not giving up on this non-disparagement clause.”

The article in The Information, published in late June 2017, cited on-the-

record accusations from three women—all tech executives who had been seeking Caldbeck’s advice or investment. In the article, Caldbeck denied the “attacks on my character.” When his PR representative emailed him, the representative wrote, according to Teo’s motion, “It’s not great, but could have been much worse. The allegations do not amount to anything even remotely egregious.”

But they’d misjudged. Ripples of complaints about women’s treatment in the industry were becoming a wave. The day before the story ran, Travis Kalanick, cofounder and CEO of Uber, resigned after reports about the discriminatory workplace there, including harassment. The Information article caught on, and later in the day, Caldbeck publicly apologized. The next day, influential entrepreneur Reid Hoffman, a LinkedIn cofounder, wrote a lengthy post saying Caldbeck’s alleged behavior was “immoral and outrageous.” That same day, Caldbeck took a leave of absence, saying, “It is outrageous and unethical for any person to leverage a position of power in exchange for sexual gain—it is clear to me now that that is exactly what I’ve done.”

Three days later, with investors revolting, Caldbeck resigned. A third partner, who’d started weeks earlier, also left. Teo said in a Facebook post that he’d “heard rumors about him from the past,” but had thought Caldbeck “had changed.” Then Lai filed her lawsuit. Around the same time, investors voted to suspend operations of the Binary funds, and Teo resigned soon thereafter. Binary was done for.

More industry-wide repercussions followed. Following a New York Times article with several women in tech going on the record about harassment and pointing to two other high-powered venture capitalists’ behavior, one resigned, and the other offered a public apology. Lai wanted more. “The biggest thing I always told my lawyer is we’re not giving up on this non-disparagement clause,” she says.

Her stance drew attention. In July 2017, the Times ran an article, “Abuses Hide in the Silence of Non-disparagement Agreements,” citing Lai’s lawsuit and showing how this was a tech-industry problem. Then, in a huge move, California passed a law in 2018 prohibiting non-disparagement agreements that would prevent an employee from discussing workplace harassment and discrimination. New York and New Jersey have passed similar provisions. Last year, California broadened those protections to prevent them in severance agreements, too, in a new law that took effect in January 2022. The bill’s name? “Silenced No More.”

Now that potential clients could Google Binary, even if Lai still couldn’t discuss it, she received more interest in her VC-consulting skills. She left Facebook, signing up a few start-up clients, whom she advised on growth, development, and data analytics. Mayer, from former Binary portfolio company Havenly, was one. She’d been impressed by Lai at Binary, and later wondered whether she could have done more to help her, especially given the aggressiveness—though not harassment—Mayer had witnessed from Caldbeck. “I felt she’d shown a lot of fortitude in walking away and taking a fairly principled stance, sometimes at the expense of her own career,” Mayer says.

In 2019, as her lawsuit dragged on, an investor Lai had done some work for recommended her to Paul Martino, cofounder of Bullpen Capital. Lai’s data expertise was impressive, Martino says, and she addressed Binary—“this elephant in the room”—skillfully. “She was just super matter-of-fact: ‘Stuff’s going on, bad things happen, I was right to do what I did. Let’s talk about what we need to do here at Bullpen,’” he says. Within the industry, Binary’s spectacular implosion had drawn serious attention. “I certainly heard the, ‘Oh, finally, somebody said something,’” Martino says. He asked Lai to use data to find promising companies Bullpen had overlooked. She steered it toward companies, like Hemster, often founded by women or people of color. And in October 2020, Bullpen asked Lai to become its third partner. After years of instability, she had finally landed firmly back in the industry, and this time, at a senior level.

Lai’s case was finally settled in the summer of 2020, with Lai receiving an undisclosed amount. A separate settlement Lai reached under California law routed some money to employees who’d also signed the NDAs; more importantly, the settlement declared that Binary, Caldbeck, and Teo could not “take any steps” to enforce those NDAs. Lai could now talk freely about Binary—as she has done here publicly for the first time.

Men in Silicon Valley can be “so used to being able to bully women into silence,” Lai says. “My personality is, I will figure out a way to say something.” And now? She’s made sure other people can say something, too.

This article appears in the February 2022 issue of ELLE.