“What are you?”

If you’ve been asked this question in America, you know it’s the first word that stings the most. “What” can’t be confused with “who” and all the effortless

responses available there: name, job title. “What” implies your abnormality. It has a blunt, vaguely dehumanizing crackle with the onus on you to diffuse. And if you’re like me, you’ve fielded the question constantly, for as long as you can remember, because your half-Asian face is a beacon for strangers’ curiosity. To them, you have an appearance that urges a clarification they feel owed. It’s immediately isolating. And you can deflect or feign ignorance all you want—I whiled away weeks of a college retail job answering this question with a Lisa Simpson quote: “I’m a riddle wrapped in an enigma wrapped in a vest”—but always, the fastest way out is through. And it’s exhausting, answering it for the appeasement of others, accepting someone else’s dialogue of exclusion.

Unless you’re Mitski—then you don’t accept it. In fact, she doesn’t entertain the question of “what are you?” at all. And I don’t think I’m alone in finding solace both in her music and in her example of how to navigate this endless dialogue about race and belonging in America.

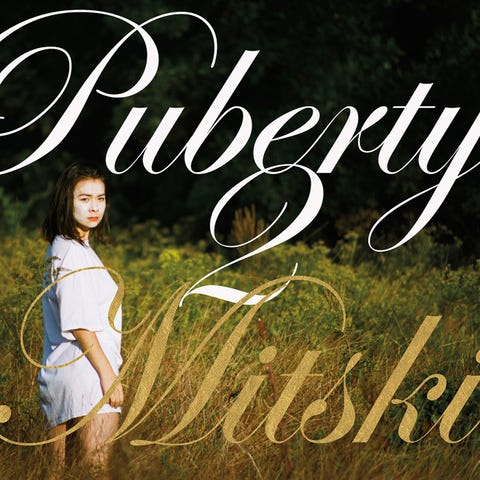

Mitski Miyawaki tells us who she is, onstage and off, with thrilling ownership of narrative. This is in her indie-rock music, abundantly; her lyrics are frank yet elliptical, capturing big, unruly emotions in the observations of smaller moments, quiet vignettes of intimacy. Her newly released sixth album, Laurel Hell, refines broad pop melodies through mercurial New Wave production, capturing isolation and euphoria in noirish still life images: a pillow pressed against a fevered face, clouds of sand swirling over a foreign horizon, a late knock on a new lover’s door. Though her lyrics don’t allude specifically to her heritage, they often prompt preconceptions all the same, because Asian women in America will always be considered through the lens of their ethnicity; listen to “Your Best American Girl,” from her scrappy, scabrous 2016 album Puberty 2, a clamorous power ballad ready to be saturated with your own ache for connection. Many fans heard the line “Your mother wouldn't approve of how my mother raised me” as a nod to her Japanese mother, the cultural friction of interracial dating in America. It’s an interpretation she didn’t begrudge them but denied its veracity all the same.

Her fifth album, the wry, technicolor tour de force Be the Cowboy, asserted her own experience from a complete opposite point of view—it was a concept album sung as somebody with brash and incurious ego, who has only known inclusion. Someone who doesn’t share her own need, as an Asian woman, to “walk into a room and feel like I have to apologize for existing.” In its scorched, heartsick lyrics, it could’ve been called “confessional,” that diluted pejorative often given to non-male artists, but aha! It wasn’t really Mitski singing, it was her fictional gunslinging persona with their shoot-first, apologize-never bravado.

Mitski understands the power of letting others project onto her, but that doesn’t mean she’ll indulge narratives that diminish her. This control extends beyond her music: It’s in the margins of every interview, in what she shares and what she doesn’t. It’s in her avoidance of the discursive trap doors set before her in the media, that I certainly recognize as a Chinese-American woman. Like the leading questions about her biracial, Japanese heritage or her feelings on being such an artist in America—which are likely well-intentioned but reinforce a narrative “otherness.” These questions carry an impossible burden: Every time Mitski, arguably the most successful Asian woman in American indie-rock, is asked to speak to how it feels to be an “Asian-American” woman or artist in America (and she has been, consistently), she runs the risk of cultural conflation. The subtext is she’s being prompted to speak to the monolith of all Asian experience in America—the dozens of disparate ethnic groups and the hundred-plus languages that lack a unifying cultural shorthand yet get flattened under that one straining umbrella term, to significant social and economic consequences. It is a monolith that no one person could ever hope to represent, yet a monolith that American society regularly dismisses and derides.

Mitski understands the power of letting others project onto her, but that doesn’t mean she’ll indulge narratives that diminish her.

I admire how Mitski answers these questions: She doesn’t. The evidence is right there, in article write-arounds of her polite but firm demurring, her savvy avoidance of the pull-quote. (She’s acknowledged as much: “I talk about being Asian and then that becomes the article,” she told Complex in 2016. “When other young Asian girls hit me up about what it is like or what my music might mean to them, then I talk about it all day.”) If she engages with the conversation, the narrative of novelty, of aberration, could endure; if she rebukes it, an outdated dialogue would carry on. I And although another artist might give a perfunctory answer, and it would certainly make sense why, Mitski spurns the exchange. It’s not that she refuses to engage at all, or is a churlish interview; she has shared some details about her upbringing outside America, feeling lonely between cultures, and referenced racism and sexism she’s experienced as an artist. But read any recent interview with her and see the trail of conversation about her ethnicity runs cold quickly; she’s as likely to muse about it at length as she is to share her debit card number. It’s like she’s answering the dreaded “what are you?” for all of us: “I am more than this question.”

Mitski’s opacity—her resistance to label her personal identity despite the intimacy of her art, in a time so many people want to turn it into headline—feels like it reflects women like me, who are proud of our heritage but anxious about how it codifies us in America. Maybe it’s as simple as we’re just afraid, and we know that demeaning language can be prelude to greater threat. As the past two years of shown, in their heartbreaking rise in violence against Asian-American and Pacific Islander communities, we have reason to fear escalation of the degradation we’ve long felt. I’m warier than ever that strangers will define and diminish me by my appearance, will approach me with an unprompted comment, because I’m no longer just wondering if I represent the usual submissive and fetishistic stereotypes to them: I’m looking for a glint of malice in their eyes, too.

Here comes the caveat that I don’t know Mitski, have never interviewed her, and can only guess her motives for anything. She could think I’m misguided and clinging to her example with the stubborn zeal of a cat up a tree. Or she may suspect, as I am right now, that it’s a bit hypocritical to admire someone’s boundaries and then dissect them for an entire essay. Yet I’ll maintain that Mitski’s example here is a valuable contribution in this moment in which many powerful Asian women are pushing back publicly against discrimination and hate—Naomi Osaka, Rina Sawayama, Cathy Park Hong, Sandra Oh, to name a few—and to infer anything but deep consideration behind her actions would contradict the incisiveness that is the cornerstone of her music; one of her great songwriting charms is that every note feels intentional, every guitar skitter and torchy vocal tremble meticulously placed. She is both a disciplined lyricist and technician who balances tension, tenderness, aggression, and the odd splash of