In the first of the two-night Lifetime and A&E documentary “Janet Jackson,” in which the iconic pop star chronicles her public life, there’s a rare clarifying moment about what the audience

is engaging in, precisely. Jackson, ever soft-spoken and slow to reveal anything personal beyond the melodies and verse of music, says, “I wanted my own identity, but at that time, my father was in charge of my life, my career, and he was my manager.”

With eyes closed, as if reliving an agonizing memory, a streak of discomfort escaping the soft expression on her face, she continues, “There are things that I wanted to do…and just the direction that I wanted to go and…like I said, it’s hard to say no to my father, so in order to do things the way I wanted to do, I guess he would have to be out of the picture.”

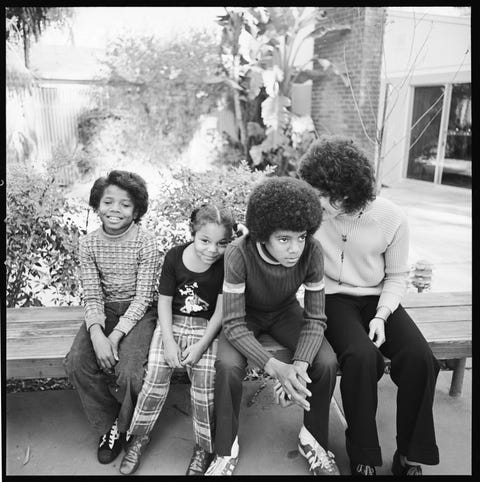

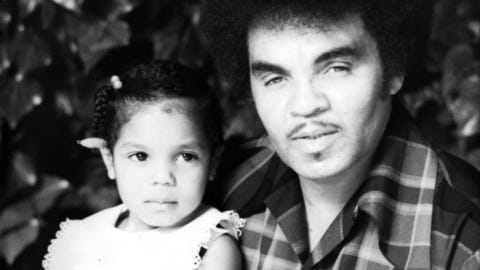

This version of Jackson, who seems almost apologetic in the scene, appears in contrast with the one her brother Tito later describes, with Janet being among the few in the family who stood up to their notorious patriarch, Joe. Throughout the Jackson family’s public life, Joe, who died in 2018, has, at best, been characterized in the public imagination as a dogged figure who used a firm hand and whatever means necessary to propel his family to greatness. At worst, his famous children, including Jackson, Michael, and La Toya, alleged he physically and emotionally abused them (a charge he repeatedly denied). The Guardian posthumously dubbed him “one of the most monstrous fathers in pop.”

It’s not a coincidence, then, that Jackson, whose ascent to pop music stardom took on a new life with the release of her third studio album, “Control,” concedes that her pursuit of independence comes as a reaction to a long line of men trying to exert power over her, beginning with her father. And while, alongside the rest of the documentary, which consists of footage of new and archival interviews, this is not a particularly revelatory detail in an extraordinary life, it does confess something else: Jackson’s use of privacy is not only a carefully constructed posture in response to fame at an early age, but also both the means—and the end—she’s sought and achieved for the better part of her life. Arguably, aside from close readings of her music, this control via privacy is always present in her romantic relationships, in her famously close relationship with her brother Michael, and even all these years later, in how she perceives Joe.

At several points in the documentary, Jackson expresses understanding, if not admiration, for Joe and his form of “discipline.” In particular, she commends him for protecting their family, the work ethic he passed down, and the vision for her siblings and herself that they would otherwise lack, she says, without him. She stops short of wholeheartedly attributing her success to his methods and, most importantly, leaves unsaid what those methods were.

Jackson also positions her parents as products of the era, who were raising children amid the difficult race and class realities of Gary, IN. Their parenting style, severe even in the context of a bygone era, can seem downright cruel by today’s standards, but Jackson expressly notes of her parents that “discipline without love is tyranny, and tyrants they were not.”

In our era of therapy speak, the impulse to psychoanalyze Jackson here is boundless, as is the desire to codify her perspective in the language of trauma. But it also feels true that Jackson can hold multiple truths about her father—Joe, the domineering father, as well as Joe, the visionary; in her mind, the two coexist and are perhaps not even a contradiction. Still, when a young Jackson imagined what she wanted from her life and career—which was to be the master of both—she knew she would have to curtail Joe’s influence over all spheres of her life. The musical resultis 1986’s “Control,” which propelled her to a status in pop culture beyond the stardom even her last name provided.

This separation from Joe, however, was never meant as a rebellion of youth or as a means of retribution; the decision is cast as both necessary and filled with anguish. Ultimately, it was an articulation of power that she prefers to leave obscure, because for Jackson, revelation can lead to a loss of control, which is her source of power. It even demonstrates what seems like an inherent tension between making a documentary and her desire to keep large swaths of her life to herself. As a result, the documentary is less tell-all and more “tell more,” offering her previously unknown responses to events that marked her public life.

Jackson’s limited public commentary on Joe parallels dynamic with her legendary King of Pop brother, who, similarly to her father, occupies a dual image of monster and maestro—Michael, who died in 2009, was accused of child sexual abuse. In an on-screen interview in the documentary, Jackson acknowledges that their relationship wasn’t the same and that they were no longer close after he released “Thriller,” which catapulted him to superstardom, but the details are sparse; her pain is palpable but left to the imagination. And on the allegations against Michael, Jackson only offers the defense that her brother “did not have it in him.” She attests to the complications of one of the most famous sibling relationships in pop culture, but doesn’t relinquish control of the detailed specifics of how it might have affected her, her privacy and power maintained.

When Jackson imagined what she wanted from her life and career—which was to be the master of both—she knew she would have to curtail Joe’s influence.

We also see this struggle through the lens of Jackson’s romantic relationships—her ex-husbands, R&B singer James DeBarge, and video director, René Elizondo Jr., along with her ex-long-term partner, musical juggernaut Jermaine Dupri. It’s through this lens that the audience can see the full breadth of her boundaries and also how her partners repeatedly challenged them. Her marriages, which were always done in secret, were accompanied by explosive rumors and falling-outs; for any number of reasons, her partners always ended up falling short in her eyes, which challenged her sense of control over her life and her story.

Jackson’s most recent ex-husband is unacknowledged in the film. But those absences, like so many others in the film, including her sister La Toya—considered the family pariah for going against the family’s position on the allegations against Michael and going further on the abuse allegations against Joe—likely would not have made a material difference to the purpose of the film, which ends up being a testament to Jackson’s intentional unknowability.

Unfortunately, the documentary also doesn’t even serve to show Jackson in all her glory as a performer. The film is framed as a series of admissions of events that make up a life lived publicly, from an icon who a long time ago saw the power in saying less. As such, it’s tempting to wonder whether, although Jackson has found power and won control over the narrative she conveys to the audience, has she found liberation? Is she free?

That question was never going to be answered in this documentary. Her music already contains the vulnerability she wants to give the public; it’s the one realm of her life where she seems willing to open the curtain, just a bit, to profess her truth. From the realizations of “Control,” to the politics of “Rhythm Nation,” to the intensity of “Velvet Rope,” to the ease of “All for You,” Jackson has been telling us about herself all this time, laying down her privacy in the form of poetry, set to varying rhythms and sounds, always soulfully sung.

We’ll never fully know Jackson from a collage of interviews from her or even those closest to her, but our best chance is the place she’s always escaped her control and let down her privacy: her music.