Carla Barrientos was 19 when she first started working at the Abercrombie & Fitch at the Valley Plaza Mall in Bakersfield, California. It was the early 2000s, and the brand’s moose-adorned

clothing and suggestive marketing were the pinnacle of cool. But when Barrientos, reportedly the only Black employee working at the store, was unceremoniously given after-hours shifts and then fired, she joined a class-action lawsuit against the company. In June 2003, she, along with eight others, sued Abercrombie & Fitch for race and sex discrimination. The company settled and admitted no guilt, though it was required to pay $40 million and sign a consent decree to change its practices and promote diversity across the brand. However, A&F’s leadership stayed intact, including its controversial then-CEO Mike Jeffries. Now in Netflix’s new documentaryWhite Hot: The Rise & Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch, Barrientos joins two other former plaintiffs to tell their side of the story. Below, she shares, in her own words, what happened all those years ago—and what she thinks of A&F’s newfound popularity.

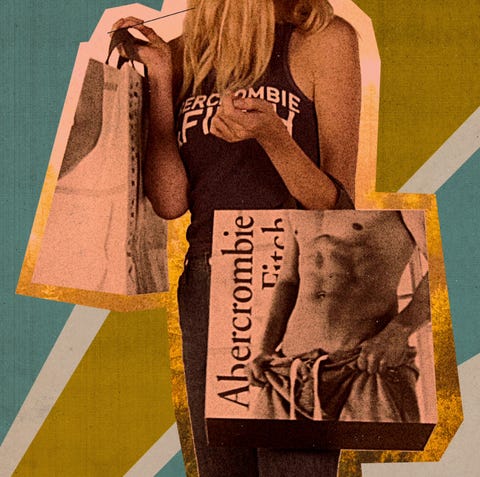

The first time I went to Abercrombie & Fitch, I heard the store before I could see it. I was walking through the mall, shopping with my family, when I heard loud house music. Boom, boom. When we actually got to the store, I could smell Fierce cologne, and I saw the guys out front with no shirts on. That was my first dose of Abercrombie & Fitch.

Back then, for me, the brand represented cool. People noticed if you were wearing Abercrombie & Fitch. If you had an A&F shirt or jeans or even a belt, it was definitely not lost on anyone. It’s what everyone was wearing.

One day I was shopping at the store when I was approached about working there. I had my little interview where I sat on a couch, and they asked me odd questions, nothing that really had to do with working at a clothing store. I had a friend who worked there, so when I started, I would walk around and chat with my friends and the managers. It wasn’t the kind of job where, if I saw a friend and wanted to have a conversation, anyone would stop me. It was fun; I’d float around, straighten clothes here and there. But then after a few shifts like that, my job started to change. Suddenly, my shifts were starting later, and I’d mostly be working when the mall was closed. Then it changed where, if our mall closed at 8 p.m., my shift would start at 8 p.m. There were a lot of cleaning duties, like vacuuming, dusting, cleaning the windows. No one had told me they were going to make this change or why they were doing it. It wasn’t what I’d been hired to do, so I knew something was going on. I just didn’t know what.

One day, I was venting to my friend who worked there, and I told her, “I want more day shifts. I don’t have any.” I had gone to the manager and asked for more, and he had told me there weren’t any to give. But my friend told me that wasn’t true. She said they’d scheduled her for 30 hours in one week, even though she said it was too much. She told me, “Let’s do this: You take my day shift. I’ll take your night shift.” Easy. Same amount of hours, we were getting the same pay rate. So I went to the manager and told him my friend was willing to swap. But he flat out told me, “We cannot do that. The shift you’re assigned is the shift you’re assigned.” It didn’t make sense. When I told my friend what happened, she said, “It’s probably because you’re Black. You’re the only Black person who works here. During the day shift, it’s all white.”

“I was so confused. How do you work at a place, but you’re not getting any hours?”

I knew what she was saying was true, but I didn’t want to face that reality. But after I asked my manager about swapping shifts, everything changed. I wasn’t on the schedule at all anymore. I was so confused. How do you work at a place, but you’re not getting any hours? I was told to just keep checking back, but when I wasn’t on the schedule for a couple months, I knew I didn’t work there anymore.

There were times I’d doubt myself. What did I do wrong? Was I not persistent enough about what I needed to do to change as an employee? I’d never want to be seen as someone with a poor work ethic. I’d never want to leave a job in bad standing. It was difficult to realize there wasn’t anything I could’ve done. It wasn’t because of something I could change; it was about who I was as a Black person. It was really painful. When I heard Abercrombie say it had an “all-American look,” I saw myself in that. I saw other people of color. I saw other folks who don’t fit what Abercrombie thought was “all-American.” It was difficult trying to process that.

Not long after I was fired, my sister told me there was a lawsuit being filed against Abercrombie & Fitch. I called this number connected to the case and left a message, briefly sharing what happened to me. Within 10 minutes, I got a call back, and they asked to hear my story and let me know I wasn’t alone. Sometimes I’d thought, maybe this is an isolated situation. It’s just this store or just this area. It was validating to hear I wasn’t alone, but it was scary to think this was a systemic practice, that this was how they operated. I never thought a company would go this far to be so exclusionary. I’d been working since I was 15 years old, and I’d never had a situation like that in the workplace, where I was discriminated against and then subsequently fired.

The lawsuit was a long process. We had to answer so many questions, and we were being gaslighted by Abercrombie & Fitch’s lawyers into thinking, this wasn’t discrimination. You just didn’t have the “look,” and the look didn’t have anything to do with you being Black. The look had to do with attractiveness. It was grueling.

“We were being gaslighted into thinking, oh no, this wasn’t discrimination. You just didn’t have the ‘look,’ and the look didn’t have anything to do with you being Black.”

Then, after it was all done, it was difficult to hear the company had admitted no wrongdoing. But I really believed they would follow the consent decree and make those changes as a company. I thought that it’d be positive from here on out. It was very disappointing to see it was not done, and the oversight was really lacking. Our case helped, but it didn’t change the company.

When change happens, it has to be real. That means dismantling the problem and bringing in totally different people. After our lawsuit, everyone who was in charge when all these terrible things happened continued to run the company. But I think there’s an ability for second chances. And now, it seems like in the past few years, the company really has changed. It’s become popular again, and for good reason; it’s very inclusive. I’ve visited the website, and it’s beautiful. I see lots of different people represented, people of all sizes, shapes, colors. When I worked there, Abercrombie & Fitch thrived on exclusivity. If you were cool, you could be here, and if you were not, you go. Now it really seems that everyone has a seat at the table. Everyone can be here, and everyone is celebrated for who they are. That’s not a negative. It’s not something that downgrades a company or a group; it enhances it.

Now I dress a lot differently than I did back when I was 19. But I’ve heard Abercrombie & Fitch has some good clothes. I haven’t been back to the store yet. But maybe next time I’m in a mall, I’ll go.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Watch White Hot: The Rise & Fall of Abercrombie & Fitch on Netflix now.