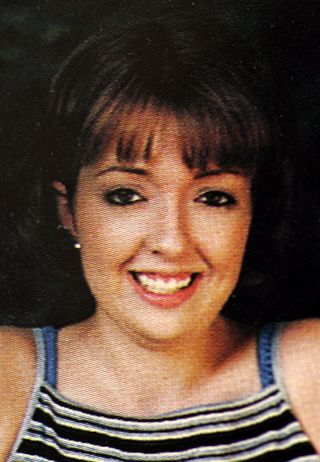

One week before Christmas in 2004, a pregnant 23-year-old dog breeder named Bobbie Jo Stinnett was strangled to death at

her home in Skidmore, Missouri. Under the guise of purchasing a puppy, Lisa Montgomery set up a meeting with Stinnett. Once inside her house, Montgomery killed Stinnett and then removed her 8-month-old fetus with a kitchen knife. Montgomery, a mentally ill woman with childhood trauma stemming from years of rape and physical assault, fled with the baby and tried to pass it off as her own, proudly announcing the “birth” of her daughter to friends and family.

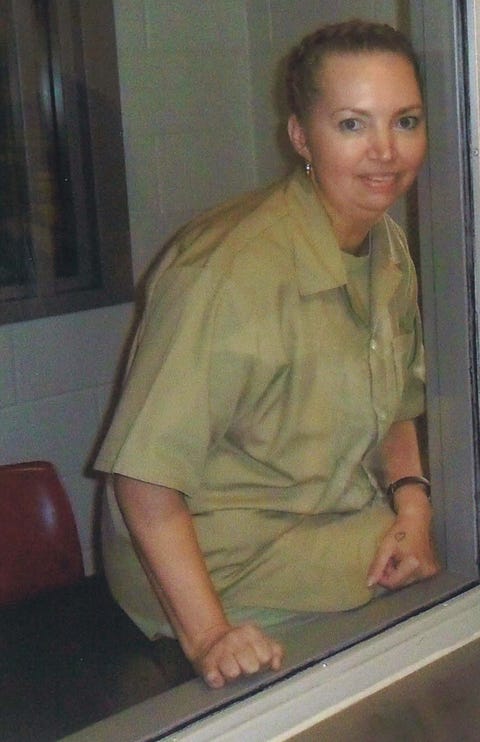

Almost exactly 16 years after Stinnett’s murder, Montgomery, at age 52, is set to be executed as early as December, making her the first female federal inmate to die by lethal injection since the Trump administration resurrected federal executions in July. Her lawyers say she is diagnosed with bipolar disorder and complex post-traumatic stress disorder, and regularly dissociates and hallucinates. Below, Montgomery’s 57-year-old half-sister Diane Mattingly opens up to ELLE.com about her sister's tragic past—and why she thinks sparing her life can "break the chain of evil actions." Mattingly's account of the abuse she and Montgomery both endured growing up was part of her testimony in court in support of Montgomery's unsuccessful motion to vacate the death sentence.

It was a drizzly morning in Ogden, Kansas. I was eight years old, living in a trailer park with my abusive step-mom Judy who, after screaming on the phone for what seemed like an hour, was now squatting down in front of me. “Well,” she hissed in my face, “they’re coming to take you away, hope you’re happy.”

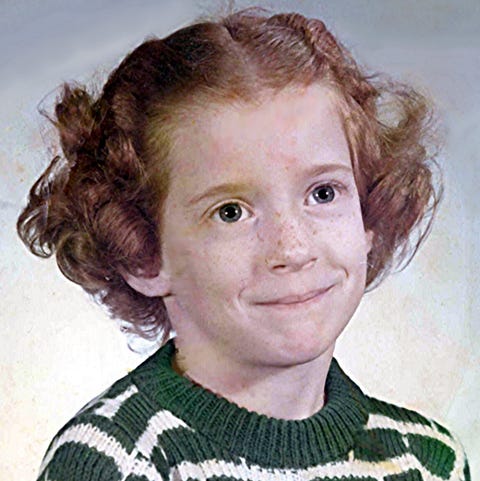

I was. In fact, I’d never been happier. But when two child protective services workers knocked on our front door later that day, my heart sank to my stomach. I was finally going into foster care, but Lisa, my little sister and best friend, was staying behind. She was four years younger than me, with wispy hair, and a sweet demeanor. When I turned back to take one last look of her, there was terror in her bright green eyes.

That was 1969. I didn’t see Lisa again until 2007, when I testified at her sentencing hearing for brutally murdering a pregnant woman named Bobbie Jo Stinnett; she cut the baby out of Stinnett’s belly with a knife. On the stand, Lisa looked just as scared as the day I left her 36 years ago.

My sister has been sentenced to die for her crime. If executed, she will become the first woman to be federally executed in the U.S. in 70 years. I will always love her, but what she did was the most awful thing a person can do. Lisa should spend the rest of her life in prison, no doubt, but she shouldn’t have to die. Because maybe if she hadn’t been failed by the people she needed most in society, she could have been part of it.

My whole life changed the day Lisa came home from the hospital. She was itty-bitty and so beautiful. Judy had her all wrapped up in a pink bundle, and when I squeezed her hand she looked at me and smiled. I fell in love immediately.

My dad, who was in the military, wasn’t around much, so I helped Judy take care of Lisa. When she outgrew her crib, she moved into my room. Our twin beds were so close they practically touched, and most nights we fell asleep holding hands. Judy didn’t allow much music or television in our home, but we did have one tea set for playing “house.” It was always me as the mom, and Lisa as the daughter.

As we got older, Judy became abusive, hitting us with brooms and belts and whatever else she got her hands on. I stepped in to take the brunt of it. She would poke her finger into my chest over and over in the same spot until it bruised. She forced me to eat raw onions until I cried. She would beat us and scream.

Worse than that was Judy’s ability to find out what hurt you most and use it against you. For me, it was a fear of abandonment. When I was six, Judy ordered me to strip down naked, leave the house, and never come back. I waited outside in the freezing cold, before she finally opened the door to let me back in. I can’t tell you if it was 5 minutes, 10 minutes, or 30 minutes, but I was out there alone, and so scared.

Protecting Lisa became my sole purpose in life. I shielded her from the random babysitters, often older men, Judy left us with for her near-nightly outings to the bar. When one of them came into our bedroom and raped me, I prayed Lisa would be safe from him.

Periodically, Judy would drop me off at a friends house for a few weeks. When I turned seven, I stayed with another family for nine months. The day I came back, Lisa ran to me with open arms like I had just returned home from war. She had endured unimaginable abuses in my absence. When child protective services picked me up six months later, she would suffer even worse.

I vomited violently the entire hour-long car ride to my foster home in Salina. My new family wasn’t rich by any means, but they had a beautiful home with lots of books, toys, puzzles, and games. My room had pink walls adorned with landscape paintings. The sheets on my bed were floral print. The first thing I did was put a framed photo of Lisa on my nightstand.

I’ve always considered myself bruised, but not broken.

Zella, my new mother, had a beautiful warmth to her. Her husband, Floyd, a schoolteacher, instilled in me the importance of getting a good education. They had three children who treated me like I’d always been their sister. We played together and chased each other around, and, on occasion, fought like siblings do. I grew to love reading, devouring mystery novels on weekends. On my first Christmas with them, Zella and Floyd bought me a pink Barbie van. I rode that thing all around the neighborhood.

I’ve always considered myself bruised, but not broken. I still can’t eat onions, or be in small spaces with men. But I have self-worth, and that’s because of certain people, like Zella and Floyd. For the first time in my life, I was happy. But I also had a big secret. I thought if my new family knew how damaged I was—if they found out I’d been beaten and raped—they wouldn’t want me anymore. So I decided not to tell them; to this day, it’s my biggest regret in life.

If I did speak up, maybe Zella and Floyd would have gone back for Lisa. Maybe she could have been saved, too. Instead, she suffered a lifetime of mental, physical, and sexual abuse—and it wasn’t just during her childhood. She was abused as a teenager and well into her adult life, too.

I never stopped thinking about Lisa. I tried to track her down once, but Judy moved them around 16 times after I left. When I met my future husband in 1998, I told him all about my long lost baby sister—how beautiful she’d been, how smart, much I missed her.

One month after our wedding in 2006, a lawyer called me out of the blue asking if I was Lisa’s sister. I couldn’t believe it. “Lisa!” I screamed with joy. “How is she? I want to see her!” There was a long pause before the lawyer said, “You can’t. She’s being accused of murder.”

A part of me always worried that Lisa suffered greatly after I left. But when an investigator visited my home three months later, I learned that she hadn’t just suffered—she had been tortured. Judy and our dad divorced, and she remarried a man who repeatedly raped Lisa and arranged for his friends to rape her, too. During her trial, Lisa’s cousin said in a sworn statement that those men beat her if she “did it wrong,” and urinated on her afterward.

I was only eight-years-old when I left her, and I know there’s not much I could have done. But it’s impossible not to feel an overwhelming sense of guilt that maybe, just maybe, if I’d spoken up all those years ago, Bobbie Jo Stinnett would still be alive—and my baby sister wouldn’t be on death row.

We reconnected while Lisa was in prison awaiting trial. I wrote to her about my husband, my job, my friends, my children. She told me that she thought about me often growing up. She kept a photo of me on her nightstand, just like the one I had of her.

After Lisa was found guilty in 2007, I testified at her sentencing hearing. She looked so much like my eldest daughter, with the same sea-green eyes, recessed chin, and high cheekbones.

It didn’t take long for the jury to decide her fate. The next day, Lisa was sentenced to die. I screamed until I couldn’t scream any more. Didn’t the jury understand that she is ill? It’s hard to keep track of all the times she has been let down by people she’s supposed to trust. Her mom and her dad. Her school teachers. The police. Social Services. Me. Now her government was failing her, too. My heart goes out to the family of Bobbie Jo, of course it does, but we need to break the chain of evil actions.

Sometimes I wonder what my life would have been like if I hadn’t escaped Judy’s home. Would I have turned out like Lisa? The thought scares me a lot. All I can do right now is pray that, for the first time in Lisa’s life, someone does the right thing and says, “I will stand up for you.”

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.