Consuming culture online is an easter egg hunt. Much cultural commentary—criticism, even—has become a sort of conspiracy theorizing, as we find signs and symbols and string them together in hopes of

finding greater meaning. Even when the parts don’t add up to a whole, the mere discovery of them gives us a thrill, and a sense that there is indeed order in a world that seems to lack it. Think Marvel movies, and maybe also QAnon.

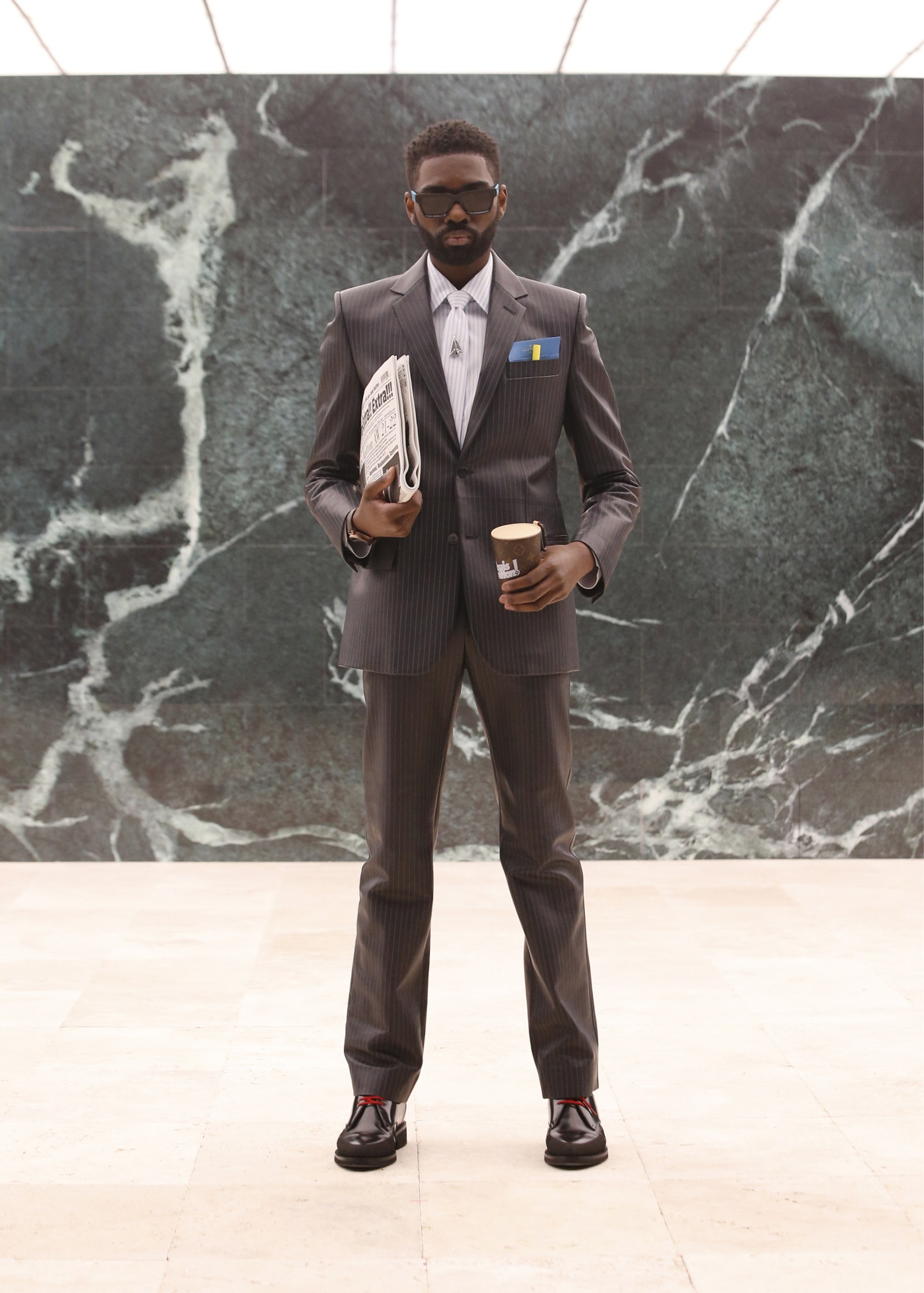

I thought about this while taking in Virgil Abloh’s Fall 2021 show for Louis Vuitton, an exploration of male archetypes: “the Artist, the Salesman, the Architect, the Drifter, etc.,” the show keynotes stated, though in the collection, I also saw the prophet, the pimp, the zaddy, the manager, and the Gstaad Guy. (Not a joke: Abloh is one of my fellow followers of the Instagram guilty pleasure @TheGstaadGuy.) In part, this archetypal approach was an appreciation of the major role that Abloh plays as the leader of a major luxury house: he has to be an image-maker, and every look has to be a grand gesture. He’s been working since last summer with the stylist (and new Dazed editor) Ib Kamara, who is also a maker of monumental, powerful images. Everyone Kamara styles seems to look like a king, and this collection had that same quality, a feeling of solemnity and eternity.

Like most of Abloh’s collections, this one was jam-packed with ideas to the point of pretension. Abloh divides critics and fashion fans, with the main critique being that he overloads his clothes with half-baked ideas and concepts, never giving any of them enough time or attention to fully develop. In this one alone, there were Lawrence Weiner aphorisms, a James Baldwin essay enmeshed with an art heist theme, a model plane motif, an original score with a Saul Williams spoken word piece, a Mos Def performance (!), paper dolls, hats inspired by Edward Scissorhands, people dressed as entire cityscapes, morning commute choreography, and John Berger quotes. It’s a lot of muchness. The show key notes said that the collection asked, “Who can claim art? What defines low vs. high? Who gets to make art? Who gets to consume it?” Great questions, though I’m not sure how this collection in particular raises—or answers—them anymore than his previous work.

Increasingly, I feel that’s the point. Abloh is hyper-aware of the way the online commentariat functions, especially among young men, and fills his collections with these easter eggs because he knows it’s the lingua franca. Maybe the only way to channel subculture now is to present so many ideas that each idea becomes a niche unto itself. Abloh is a notorious online explorer, an autodidact in the world of fashion, and more and more his collections function as encyclopedias of hidden messages and references, full of gestures meant to inspire obsessions and rabbit-holing among his followers. The big narrative isn’t necessarily the point. I could be wrong, of course, but tellingly, Abloh included a new phrase in the book of terms he updates each season: go fish, which he calls “an innate reaction of human beings when first gazing upon an object to relate it to something they’ve seen before—often before seeing the nuance of the object.” That’s exactly what I’m talking about here. The result is that thinking hard is framed as a luxury object in and of itself—the kind of semi-bogus idea I think Abloh would love.

Kim Jones is the other designer who has to work—or maybe I should say, works successfully—in this “big image” way, envisioning the major fashion house he helms, Dior, as a platform to educate young men about his passions (Judy Blame, Shawn Stussy), the intersection of streetwear and the art world (Daniel Arsham and KAWS), and the technique of making clothes. He’s much more concerned with beauty, and the process of making complicated garments, having taken advantage of his access to the Dior couture atelier to make things like sheer shirts embroidered with his favorite artists’ motifs and elaborate novelty knits. There is a long history of laboring over seemingly impossible garments in women’s couture, and I can’t think of another designer who has approached the idea in menswear from a couturier’s point of view, rather than a tailor’s. You can see how and why an art fair prince would gravitate toward Jones’s pieces.

For this collection, he worked with Peter Doig, a genius Scottish painter who is much more of an art world doyen than his previous artistic partners like Arsham or Kenny Scharf—much more Artforum than Hypebeast. These clothes had a serenity that only a painter at Doig’s level of technical superiority can elicit: the knits (some quoting directly from Doig’s work), the soft tailored trousers, the sublime satin coat painstaking printed with Doigisms. Jones also changed up his silhouette, which has been fitted and precise since his first collection in January 2019. Here, he worked with the foundation of a fitted, military-inspired standing collar jacket, and a soft, almost blousy trouser. It was confident and spiffy in Doig’s washed tones—especially in the finale look, under an opaque purple fur coat, with bracelet sleeves and a big spangly brooch.

These are two designers who don’t have to answer to the state of the world—who can instead make fashion for fashion’s sake because they are operating at the peak of their craft and, we must admit, their powers. And they’re a reminder that the world's royalty isn’t only to be found on the slopes of Gstaad. Though you’ll certainly still find them there.