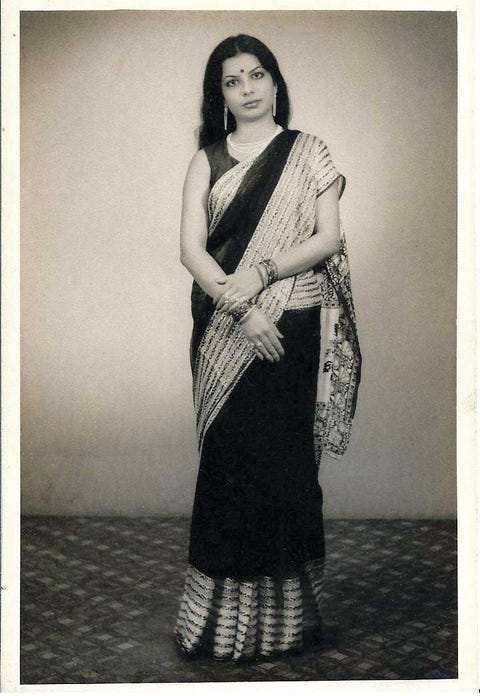

Priyanka Chopra Jonas comes from a culture that doesn’t exactly encourage women to talk publicly about their personal lives—much less publish books about them. “It was ingrained in me from a

young age not to air my dirty laundry in public,” she relates. “What’s another way to say it?” she asks, but answers her own question: “How about, people shouldn’t see you polishing your dirty armor—or something along those lines,” she laughs. “I grew up with that one, too.”

When Chopra Jonas was thinking about writing her memoir, her plan was to let people read between the lines. “I initially thought the book would be a series of letters to my younger self,” she recounts to me via Zoom. It’s a mid-January evening in London and Chopra Jonas is sitting serenely in front of a large burning fireplace wearing a two-tone silk shirt, her hair pulled back from her face. “I started the process in early 2020 thinking I would talk about my achievements, my laurels, give advice to my younger self—that sort of thing. I thought I would scratch the surface and skim over the more difficult parts of my life,” she muses dryly, shaking her head at her own naïveté. But when she sat down to write, that’s not what came out. “The process became more like writing in a journal,” she says. “As I started thinking about everything, writing became a dissection of my emotions, my failures, and my pain. There was so much that flowed out of me that I hadn’t thought about in years or even realized that I remembered.”

The task of immersing herself completely into Unfinished, her autobiography, came at the right time. “I was approaching 20 years of being in the entertainment industry and it was something I personally wanted to acknowledge,” she explains. “I also realized that I was at a place where I was self-assured enough to look introspectively into my life—something I wasn’t capable of at the time these things were happening.”

The child of military doctors, Chopra Jonas grew up moving from one army base to the next. “Then, as an adult, I was always running from one project to the next. There was never any time to look back and reflect.” I nod, thinking of her plethora of Bollywood roles over the past two decades—70 and counting. “It has always been about the next thing. In many ways, I feel as if I have been running from myself for most of my life.”

True to form, our conversation comes on the heels of Chopra Jonas having just wrapped the Sony Pictures romantic comedy Text For You co-starring Celine Dion and Scottish actor Sam Heughan. With barely a break in between, she’s about to start work on the Amazon series The Citadel with actor Richard Madden (Bodyguard; Game of Thrones) for showrunner team the Russo Brothers; the project will have her stationed in London until November. “My job doesn’t have the luxury of consistency,” she says. “So when COVID happened it forced me to sit down and address the things I had bottled up for many years.”

Boarding school was an emotional place Chopra Jonas felt she needed to revisit. “Being sent away to school in the third grade was something I thought I had put to bed, but I was compelled to reconcile with for the book,” she tells me. During her first week at La Martiniere Girls’ Private School in Lucknow, India, a four-hour train ride from her hometown of Bareilly, she recalls sitting on a merry-go-round in the school’s playground clutching the cold, rusty bars, her eyes fixed squarely on the gate. She willed her mother to come back and take her home. “What I remember vividly is the feeling of being abandoned—a feeling that lasted for a long time.” After months of heartache (including one episode that made her physically sick) and clingy visits with her mother that pushed back any progress, Chopra Jonas says she slowly started to adjust.

But as the seesaw between emotion and numbness subsided, the confusion remained. “I didn’t understand why I had been sent away,” she says. “I also didn’t understand why she couldn’t visit as often anymore.” Some days Chopra Jonas blamed the arrival of her little brother, Sid, for taking away her mother’s attention. Other days, she blamed it on her own “bad behavior”—recalling the tantrums might have triggered the decision for round-the-clock discipline. “My mother didn’t explain her reasons for sending me to boarding school,” she writes, “maybe because she didn’t fully understand them herself”. Eventually, Chopra Jonas stopped questioning why she had been sent away and started settling in, thriving in extracurriculars such as singing, dancing, drama, and public speaking—a sign of things to come. She also made close friends. “I never thought about it, but maybe it gave me a stability I didn’t know I was craving,” she tells me.

The boarding school also gave Chopra Jonas a taste of independence—something she wanted more of as a teenager. At age 13, during her first-abroad trip to visit relatives in Cedar Rapids, Iowa with her mother, she loved the sense of autonomy she witnessed during a visit to her cousin’s high school. “In India, we wear uniforms in school, but in America I could dress the way I wanted,” Chopra Jonas says. “Girls wore makeup and wore their hair down. They also wore shorter skirts. That was exciting.” When her Kiran Masi (maternal aunt) asked her if she would like to live and go to school in Cedar Rapids, Chopra Jonas didn’t have to think about it: America could offer the brand of freedom she was looking for. She wasn’t afraid of being away from home this time: “Really it felt like just the next step in my education. I felt like boarding school prepared me for America.”

What it didn’t prepare her for was the bullying and racism that cast a shadow over her new life. During her sophomore year in Newton, Massachusetts, where she lived with her Vimul Mamu (maternal uncle) and his family, a peer in the ninth grade and her squad of “hecklers” started targeting Chopra Jonas. At first, she did her best to ignore the racist slurs and casual shoving. “I stopped taking the bus because I knew they would be on it,” she writes in the book. “I took different routes to classes even though they were longer; I stayed away from where they congregated at the lockers.” Chopra Jonas tried to manage the situation by herself for a year, but her self-esteem suffered. “I was tired of being pushed around and seeing vile things written about me in the girls’ bathroom.” She called her mother and told her she wanted to come home. “I broke up with America,” she tells me.

“I broke up with America,” she tells me.

The experience woke Chopra Jonas from the juvenile, sitcom-induced infatuation for the country she thought she knew. But she’s grateful she had the opportunity to escape. “There are so many kids this happens to, but they don’t have the choice I did to get out of their circumstances,” she says. “I was lucky that I could leave and that I didn’t have to deal with it. I think that if I had stayed it might have chipped at my confidence a lot more than it did. I feel blessed that I could go back home to the support and safety of my parents.”

But she knows that “not having to deal with it” isn’t always a blessing. When her father passed away from cancer in 2013, Chopra Jonas says she never really examined or dealt with her grief. “Instead I just powered through it.” She had just finished training for the title role of the Indian film Mary Kom, the true story of the Indian female boxing champion. “Distracting myself with work has always been my modus operandi,” she emphasizes with a gesture of her hand. “Any kind of heartache, failure, grief, or loss—I always just turned to my work. Work engulfed me whenever I needed it to. I was like an ostrich: I always just buried my head in the sand.”

While the physicality of the role helped to channel some of her grief, suppressing her feelings resulted in a depression that would surface a few years later. It was the spring of 2016 and Chopra Jonas had just moved from Montreal to New York to shoot the second season of Quantico. “I thought I had moved past it,” she says when I share a little of the ebb and flow of my own grief after losing my father three years ago—who, like Chopra Jonas’ dad, was also in his sixties. She nods in understanding. “In reality, I was always carrying it with me.”

There were more unhappy endings. Quantico wrapped its final season and a romantic relationship also came to a close. “I was fortunate to be able to work because it was my salvation.” When she wasn’t on set or on location, Chopra Jonas says she was mostly alone. “I would eat alone, watch TV alone. I got very little sleep, and I put on about 20 pounds.” She doesn’t believe she was clinically depressed, “but the time felt like a never-ending slump, a long sigh of sadness, a sort of pause on life that lasted three years,” she writes. There was one notable bright spot during Chopra Jonas’ intermission from life: “It was when I met Nick, even if it was very briefly,” she recalls, referring to her now-husband, singer-songwriter Nick Jonas.

Reflecting on her past through her book has been a lot like getting therapy, says Chopra Jonas. “It was a healing process,” she says. “For once in my life, I allowed myself to feel the feelings that I should have felt at the time.” In typical Indian fashion, her worrying has found a new outlet: the book’s release. “I’m terrified. There’s so much in there that I’m not comfortable sharing, even though I just did!” she laughs heartily. “The book is still fresh in my mind—raw even—especially since I just finished listening to the audio version. The whole time I was thinking, Ohmy God, how am I even talking about these things?” She jokes that there are at least 25 things she wishes she had taken out. “But you know what? It’s okay,” Chopra Jonas says. “I understand that I can’t always be in control of everything.” She pauses, then adds: “It’s also too late to stop the presses.”