I woke up in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Then went to Iowa. I stayed in Iowa about three hours longer than

I’d planned because I visited a Mosque, and by that time I couldn’t do the six-hour drive to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, my next planned stop. Exhaustion combined with the need to keep moving west drove me to Rochester, a spontaneous destination: It was about three hours from Dubuque, and it had a Marriott.

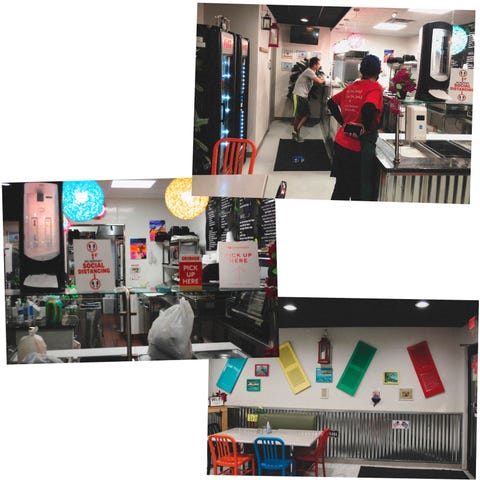

I got there around 6 p.m. and began my now-customary wandering. I passed by a dimmed neon Motel sign, a smoothie bar, and the Mayo Clinic before the bright lights of Francisco’s popped open my eyes. The window shutters in tropical colors beckoned me. Behind the counter was a Black woman with sweet, expressive eyes and a happy, round face.

“What do you recommend?” I asked.

She turned and flung her eyes up at the menu. “The…jerk chicken! The pork,” she said, scanning. “Hmm—you can do a plate. Get the coconut rice.” I thought coconut rice was a Nigerian dish only my mother cooked. My interest in this place grew.

“Yellow rice, too. Let’s see. Empanadas. The oxtails,” she continued. “Yeah, the beef and cheese empanadas.”

I was thinking: How does a storefront restaurant in Rochester, Minnesota, end up serving oxtails and empanadas, a lovely Black woman behind the counter, the whole place smelling like some Caribbean dream, in a city where the average snowfall is almost double the national average, and the low temp in January is 5? And where the population is 80% white?

Make it make sense.

Another customer walked in. “Oh,” I said, turning to the white man standing behind me. “I don’t know what I want yet.” He was there for a pickup—the third within the last few minutes. Meanwhile, I had formed all kinds of questions. How long have they been here? The restaurant carried both Cuban and Jamaican food—why? Growing up in my neighborhood it was one or the other—everyone had their favorite Hispanic restaurant and their favorite Jamaican spot. Had the pandemic slowed them down? I asked all of these and more to the nice woman at the register, who promptly summoned Lisette Nunez-James, the owner and chef. She emerged wearing a stained green apron and steamed glasses.

He passed in July 2020 after years of kidney transplants and dialysis treatments.

It’s amazing, the stories we don’t know about the people behind counters across this country. The places where we pick up our empanadas or our dry cleaning; where we buy a sandwich or a box of nails; where we get our hair done or our car fixed. Especially when we do these things at small businesses. These are people with stories and experiences, some of them painful, some triumphant, or both. People who built these businesses, which is a hell of a difficult thing to do. We know nothing of this, usually. We pay. They say thank you, we say thank you. We walk out the door back to our lives and, at the end of the day, they go home to theirs.

As Francisco’s life was slipping away, Lisette oversaw the relocation to this new spot, where the business reopened in March 2020 as Francisco’s Restaurant. The downtown location is better than the food court, especially now—some restaurants from the food court have had to remain closed since the pandemic struck in March.

While they technically were an existing business, the timing of relocating and rebranding just as covid spread was…bad. “We really don't know what this place is capable of because we’ve been at fifty-percent capacity,” Lisette said. They’ve been making it with deliveries through DoorDash, Grubhub, and Uber Eats, but the commissions are steep, usually between 30% and 40%. Even if a customer orders through the app and picks-up, Lisette is still charged 20%. She had a recent victory with Grubhub: She negotiated with them to waive that 20%.

In charge are three women of color: The cashier who greeted me was Lisette’s cousin Miesha Hyatt, who also cooks. In the kitchen was family friend Daisy Lara, her graying hair up in a bun. (“Daisy does every. Thing!”) They all live together. Lisette can’t afford to hire a delivery person, but even if she could, “I'm kind of afraid to hire strangers because I don't know what they do after they leave here. There are a few businesses around here that have shut due to the covid spread. And I don't want that.”

Business has been steady—they still get support from the Mayo Clinic staff. During the summer Francisco’s was awarded the Southern Minnesota Initiative Foundation $10,000 grant from the city, “being that we're a minority business,” and the city of Rochester also covered some of their utilities for about two months at the height of the pandemic. The CARES Act came in handy for a bit, too. Lisette said it's one good thing the Trump administration did for small businesses—even though a lot of owners she knows didn't get it because it required an existing bank relationship. “A lot of small businesses were kind of a cash-run situation,” she said.

We had taken a seat at an olive-leather half booth by the entrance as more people walked in for pickups. Lisette sat on one of the colorful iron chairs that filled the eatery: orange, red, blue, yellow. The restaurant’s logo coated most of the wall: a painting of a classic 50s car with bugeye headlights, a Cuban flag as its license plate, and a rising sun at its rearview, “Francisco’s” in bold blue letters.

Lisette is Dominican and has lived mostly in New York and Miami, where she met her husband, Jeffrey. Those cities felt like bubbles because she found herself in communities that looked like her. “But coming here really opened my eyes. My eyes should have been open a long time ago, but I never ever felt that,” she said. “And then it came even more through my daughter.”

Her daughter is mixed-race (Jeffrey is Jamaican) and attends a “super-majority” white school. Once, Lisette said, her daughter was being bullied by several white students, some of whom called her the N-word. A few of her white friends stepped in to defend her, but things escalated, and some of her defenders ended up getting expelled. It was a messy incident. Lisette’s daughter tried to use it as a moment to talk about race at the school, but the whole ordeal “really hurt her.” Her daughter was born in Jamaica, and “in Jamaica, you’re Jamaican. Even if there’s a rainbow of colors, everybody’s Jamaican.” The closest thing to racism most people experience “is colorism, which is basically, If you’re fair-skinned you’re considered prettier, things like that. So coming here was very eye-opening for her.”

Shortly after the Francisco’s restaurant relocation, Lisette said neighbors began reporting them to the city for various violations, which were bogus, or at least, nit-picky. “My husband is adamant that it’s because we're a minority,” Lisette said. “They were really on us about things we know that if it was another business, they wouldn't care.”

That eventually stopped, and the community started supporting the business—still, there are those few who make her feel unwanted. It’s hard to say why, exactly, but it’s how she feels: “It's weird because you think about it, you’re like, Is it me? Am I being overly sensitive? Or you feel crazy! That’s the worst part. I prefer how we New Yorkers are kinda, ‘I don't like you.’ I know where we stand. People say, ‘Oh, New Yorkers are rude.’ No, they’re authentic. There’s a level of inauthenticity here that surrounds us. I’d rather know where I stand.”

What compounds it all? Being a woman and a person of color: “We got two dings against us,” she said. But this year’s energy of civil unrest, protesting, Black Lives Matter—all of it has been refreshing for her. She just wants it “to really make change.” After the chaos of 2020 passes, she said, she worries that “everything goes back to the way it was. And I don’t want it to. I don’t want the normal. It needs to all change.”

As women, we have a movement, too, that we need to pursue: “Like RBG dying. It was crazy for me. It’s devastating for me because I’m like, this is the only woman in the Supreme Court that was pushing for sexual equality amongst men, women, and everybody. Now, we have no one that represents that. It’s just so much. It’s just so much.”

Sometimes she feels she needs to be “medicated,” she said, “because I’m so just, like, overwhelmed. Trying to keep this business afloat.”

Lisette asked, “What rice?”

Miesha: “The coconut rice with peas is really good.”

Miesha was right: It was. It was all really good. I sat in the olive-leather booth and admired this food, prepared by these three women, about whom I now knew a little bit more about. When I finished, I walked out the door back into my life, and in an hour or so, they would go home to theirs.