How do I do it this time? I thought as I got closer to them, a mother and daughter

laughing at an outdoor table, shopping bags at their feet.

Should I ask for useless directions?

Ask for the best place to get shoes I don’t need?

I mustered the most cheerful voice I could.

“Hi, ladies! How are you two doing?”

It had been a day, and I was frustrated. A facemask made it hard to engage and disarm people, especially those who didn’t look like me, because I couldn’t flash a smile. But one of the women smiled big—she didn’t wear a mask—and said, “Heyyyy! How are you?” The younger one was slim with dark-lined eyelids. Her silver-haired mother looked petite, with gray eyes behind clear specs.

Her energy refreshed me. I did a quick calculation: I think I’m six feet away. I brought down the mask for about a second, just below my chin. Flashed a smile. “I love that red!” the younger one screamed, pointing to my Infallible Maybelline lipstick. “It looks so good on your skin!”

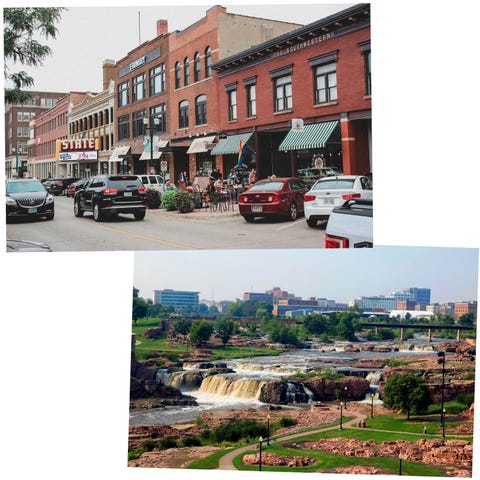

I don’t like the word hate. I’m all about getting into my feels. And I believe there are ways to unpack that word with more effective classifications. But I hated my entire day in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, before I met Jody and Jan. Never in my life have I felt so visible and seen. In the worst possible way.

I had arrived that morning and found free garage public parking right away (quite possibly the biggest difference between Manhattan and Sioux Falls). As I began walking towards an intersection, 10th and Phillips Streets, I heard rap music blasting. As it moved down the street, that bass hit me like hello! I turned and saw a white, middle-aged man cruising down West 10th, windows down, in a maroon pickup. I met his eyes. They were already on me. As he drove past, he did what felt like a quadruple-take my way. Is there something on my dress? Is it my mask?

Or was it just…me?

I shook off the truck-guy and continued.

The downtown was three or four blocks, and I did what I usually did: Tried to greet people. But I couldn’t even get someone to hold eye contact with me long enough, let alone finish my good-mornings and how-are-yous.

I stopped in a local store. I’d been looking to get a worn-in leather journal, but mainly I went in to clear my mind. From the moment I walked in, I saw the one white guy and woman at the counter in the middle follow me with their eyes. And I thought, I wish I could just disarm them with a smile.

Was I paranoid? You bet I was.

The weird thing is, looking back, I had no idea how they were feeling. Maybe they wanted to talk to me, welcome me, but weren’t sure what to say. That’s not how it felt, but I’ll never know.

This fearless woman—or so I thought I was until this day—was all like, Let’s jet. The air felt tense. I forced myself to go into Coffea Roasterie, a cute shop on the corner of 10th and Phillips, and ordered a black coffee. I eavesdropped on these two white girls’ conversation. It was impossible not to. They were right there.

“So, what do you think your love language is?”

“What do you mean?” With her back to the window, the girl closest to me sounded like the mentee in this relationship.

“You know, like touch, time spent together…”

What in the world? I disconnected from that real quick and continued on my phone. Where in Montana should I go? I zoomed in and out of the map. Billings sounded random enough. Or Bozeman. (What’s a Bozeman?) Then from there, Spokane, or maybe straight to Seattle.

“I started this Bible study on Paul,” the mentor girl said so loud, it made me think of my Campus Crusade for Christ days. Oh, I get it now. It’s like a Christian-accountability-partner-type conversation, where people new to the faith find someone deeper in the religion to help them navigate whatever feelings they’re working through. I aborted any plans to try to jump in.

“I love that red! It looks so good on your skin!”

Turned out the mother and daughter were visiting from Wisconsin to see Jody’s son play football. Jody, with shoulder-length blond hair, looked like she did yoga on her front porch as the sun rises. Jan, her mom, struck me as a power walker. They were fair white. Jody was probably 50s—I only guessed that because of her college-aged son. Jan, 70s?

They sat at a round, steel table, the kind where when you slide the chair out it makes a painful noise. Next to us were cut red, purple, and white flowers with spiky green things sticking out. It was a bright, breezy day.

These moments excited me. There are so many fascinating people out there in the world, just trying to try. Here were two of them.

I told them about my crazy project. I told them this was my twelfth stop. I asked them about their year. How’s it going?

“It was very hard educating kids in a pandemic,” Jody started. She said she was a school administrator. “Some families aren't healthy, and now they’re stuck together. That's not healthy. And you know, I have kids who we worried a lot about. It's not a healthy environment. We were their safety. They came to school with us for eight hours a day, and that was safe for them. And they lost that.”

Jody said the country had gone further and further away from teaching kids about civics and history. She was a firm believer in: If you don't learn your history, you’re doomed to repeat it. “We're not a perfect country—no place is perfect. But there are things we did wrong,” she said. But as she’s watched these past months, with people arguing over controversial Confederate and other statues, for example, she felt “people don't understand the history”—why some of these people got statues in the first place, and the symbolism behind them: “Some of the people [in history] maybe didn't always make the best choices. So that could be a reminder to learn from those people’s mistakes. Learn from that time in our history, and do things different.”

Jan didn’t say much. She nodded every now and then as Jody and I went in like girlfriends catching up over coffee. Jan felt strongly, though, that too many homes are broken. “The country is going downhill because of the breakdown of the families,” she said. The men, especially, she added, aren’t “stepping up to the plate.”

They talked about the Civil Rights movement, and comparisons between the 1960s and today. “It’s a fight between patriotism, and what's right for our country and the destruction of our country,” Jody said. Jan nodded hard to this and stared at Jody, then at me. Jody continued: “So, I pray hard. I may not agree with everything that our current president [Trump] does, but I know he will be a patriot and take care of our country.”

We heard loud music just then—a “Sip-N-Cycle” open tram with wheels going past. Five people sat on one side pedaling and drinking away and another five on the other doing the same. “Early morning party bus?” Jody said. I turned to face the cyclists. Point and shoot with the Canon. When I turned back, Jody hadn’t miss a beat.

“I honestly think [Trump] has done a lot of good economically, and things for all races,” she said. “And that greatly encourages me, and it scares me to death to think about a socialist society, where we're gonna encourage rioting and lawlessness. It scares me.”

So, I asked, what do you think about the protesting? The killings?

She thought long on this one. She looked to her mom, then back to me. The George Floyd murder was awful, just like any shooting or death, she said. “I don’t condone those things.” But, she said, we also didn’t get the full picture: “We always get snapshots of what the media wants us to see.” She believed in the judicial system to handle such injustices.

I mentioned my time in Kenosha two days ago, and the burnt car lot. Many of those scorched businesses, Jody said, were owned by African Americans. “It breaks my heart when I see people asking them to leave their businesses alone, and their own fellow brothers and sisters and my white race is out there burning them? For the sake of justice? That’s not justice. That’s criminal,” she said.

It’s the newer version of the 60s, this time with groups like “Antifa, who are trying to destroy our country.”

So, what was it like to be Jody right now?

“I'm worried because I'm white. Are you, because you're not, thinking I am racist,” she began. “I love that you stopped me. I would be kind to you if you were purple. That’s the thing that sometimes makes me double-guess people of different races. Like, do you think I’m bad because I’m a white person? I never used to think like that.”

It’s just different pigmentations, she said. “It's heart-wrenching to me to hear that because I’m white, I should now apologize to everybody because my pigmentation happens to be white, and yours is a beautiful mocha? And mine is not?”

There’s a lot of protesting going on that focuses on skin color, I said. On race. On the systemic racism that affects Blacks and minorities.

“I truly don't believe that,” Jody said. “I think it's something they want us to believe.”

“Who's they?”

“Antifa. Do I believe we have been a country that has accepted racism? A hundred and twenty percent. Do I think we have more work to do on it? I do. And I do believe in order for it to be systemic, that would mean people who are not white could never achieve anything. And I think you can see within our society, an awful lot of things that people of all races can achieve. So I don't believe that it's actually accurate.”

We make our way back to the rest of my day. I must be tired, they said. I was, but I told them once I hit the highway and cruise, it’s not that bad. I taught them how to say my last name again. “Oh-mocha.” Jody loves it. I told them it’s Nigerian—I don't think they asked. Habit, I guess.

We talk about New York and how I can never leave. “It’s been home for forever,” I said.

Jody told me I needed to move. “We would be best friends, I’m confident in that!”

Maybe we would, Jody. Maybe we would.