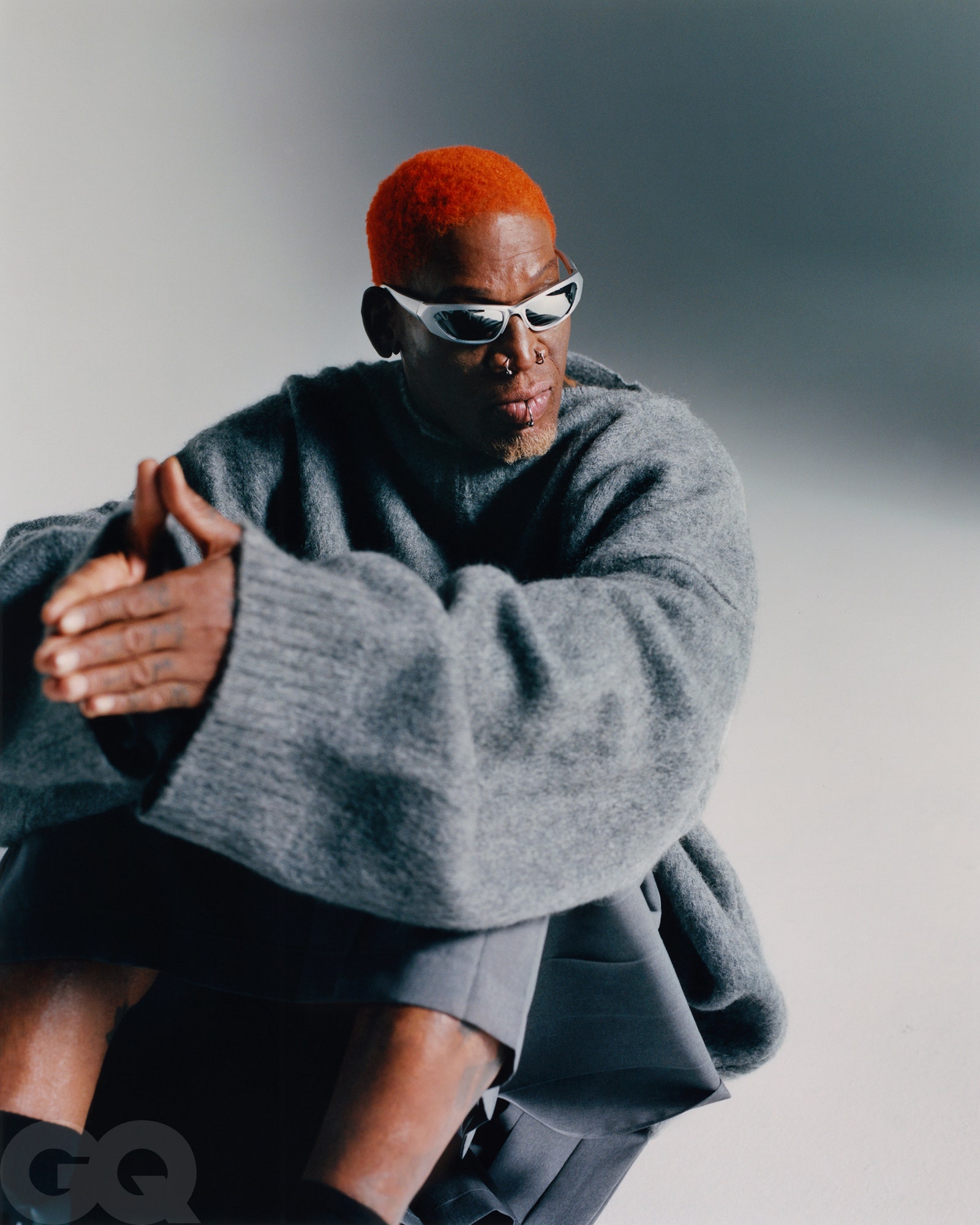

He was selected by the Detroit Pistons in the second round of the 1986 NBA draft, 27th overall, when he was 25. He had had an excellent college career at Southeastern

Oklahoma State University, even though he’d hardly played organized basketball before college. The Pistons considered him more of a project than a prospect, and given a roster stacked with Isiah Thomas, Joe Dumars, Rick Mahorn, and Bill Laimbeer, Dennis needed to find a way to stand out and make himself valuable. So he made the decision to focus almost exclusively on defense and rebounding: areas of the game that require tremendous amounts of energy, which played to his strengths.

He realized almost immediately that his motor wouldn’t be enough. In order to play defense against the league’s biggest stars—“Larry Bird, Magic Johnson, James Worthy, all these guys, legendary guys,” he says—Dennis figured he would have to study up. “I had to get familiar with how they play, so I had to sit there and focus, focus, focus,” he says. Dennis decided this was his role, then turned it into a craft, one he dedicated all of his free time to honing. He became a key part of the legendary Bad Boys, a physically intimidating, take-no-shit Detroit team that regularly beat up a young Michael Jordan and his Chicago Bulls in the playoffs. On a team of big personalities, he was a quiet, relentless grinder—an endearing fan favorite. The result was two NBA championships before Dennis turned 30. “I worked on defense every day for, like, a couple of years, man,” he says. “And all of a sudden, I perfected it to the point where I knew how players were going to react to something [before they did].”

As a basketball fan, listening to Dennis get into the weeds of defensive and rebounding strategy is thrilling, especially because it’s such an intellectual pursuit for him. Seeing Dennis’s interiority was the most fascinating part of The Last Dance, the ESPN and Netflix docuseries about the Jordan-led Bulls that debuted in the early days of COVID lockdown and, to some extent, recontextualized Dennis’s place in the culture. There’s one scene where Dennis starts to explain his self-assigned homework of learning how the ball would bounce and spin off missed shots from different players from every spot on the floor. The moment, however, was immediately meme-ified and flattened, with Dennis’s flailing arms and facial expression used as fodder for feelings of exasperation or confusion. As memes circulate and transform, the original context ceases to be part of its consumption, and, here with Dennis, something major is lost. “What the memes obscured, in very classic Rodmanian tradition, is they obscured the genius,” says ESPN’s Pablo Torre. “Like he’s telling you, ‘This is how I did it. This is my approach, and the fact that it seems insane to all of you’—and he didn’t say this part—‘is clearly because I am a savant.’ ”